In 1891, Henri Haubry was thirty-one when he hosted the renowned French anarchist orator Joseph Tortelier, who was on tour, at his home in Lilly, a small coal town in Cambria County, Pennsylvania, with barely a thousand residents.1 This county was one of the most productive in the region, with fifty-one mines employing over 5,100 miners who extracted more than 3 million tons of coal that year.2 Haubry had long condemned the poor working conditions in the region's coal mines and the mistreatment he and his fellow miners endured from the coal companies. Having immigrated to the United States from Belgium, Haubry found a small community of French-speaking miners spread across several counties in Western Pennsylvania.

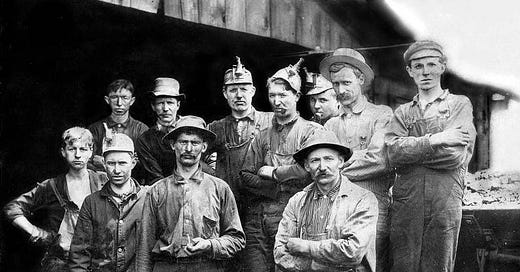

The life of an immigrant coal miner in the United States during the 1890s was harsh and precarious. In this remote region of hills, hollows, and coal camps, thousands of foreigners like Haubry toiled long hours in dreadful conditions for little pay and were often forced to live in company houses and shop in company stores. Miners constantly moved from one place to another in search of better conditions among the hundreds of small and large operators across several counties. Complaining could get you fired. “No one says anything,” wrote one French miner in 1891, “everyone is content to quietly grumble in their corner, and the situation keeps getting worse. It is especially on the backs of those who do not speak English that these dirty scoundrels fall the hardest.”3 This kind of exploitation did not make it into state inspector’s reports, which, for 1891, reported a decrease in fatal accidents but gave low marks for ventilation and sanitary conditions underground.4

Two months before Tortelier’s arrival in America, Haubry tried to rally his French and Belgian fellow miners to resist the operators. “The exploiters are counting the money they stole from us over the course of 1890,” he wrote. “They can feast, they don't need to deprive themselves of anything; our sweat brings them beautiful dollars.” He urged courage to combat the exploiters and was especially vehement against the clergy. “How is it possible that there are still fanatics who help this clerical filth survive when it should be eradicated?” He ended his plea with practical advice for his colleagues forced to beg for scraps from mine to mine:

I warn comrades who are thinking of changing places not to go to Rocky Hollow near Johnstown. There, they cheat terribly on the weight of the cars. There's water in all the rooms, and besides, it's full of rats. With a comrade, I advanced 18 meters there. The boss had promised us $1.00 per meter, and at payday, we received 50 cents; he stole $9 from us. From there, I went to Millwood Shaft. They pay 38 cents per ton there, and the coal is as hard as river coal. Then I came to Lilly; as soon as I arrived, we went on strike. If only it were the last one! How much longer will we have to travel from place to place, tightening our belts, in search of a poor piece of bread?5

Haubry’s outburst reflected his anarchist beliefs. Sometime in the late 1880s, when he lived and worked in Houtzdale, thirty-six miles north of Lilly, he adopted anarchism and became involved with a group called Ni Dieu Ni Maître (No God No Master). In 1890, he subscribed to a new anarchist periodical called Le Réveil des Mineurs (The Awakening of the Miners), launched by Louis Goaziou, a Brittany-born anarchist miner and trade unionist, who lived in Hastings, halfway between Houtzdale and Lilly. The paper found subscribers among French-speaking miners in Pennsylvania, Ohio, and Illinois. Also, in January 1890, the United Mine Workers of America emerged as a new industrial union to organize all miners without distinctions.

In March 1891, Joseph Tortelier, a cabinetmaker by trade and one of France’s most prominent propagandists for anarchism and revolutionary unionism, arrived in New York for a lecture tour. A colleague described him as “a hardworking and modest laborer who, for years, worked tirelessly to persuade his fellow sufferers of what he felt was true and just,” usually with “admirable heights of eloquence.”6 Tortelier stood out for his tenacious advocacy of the general strike, often criticized by insurrectionary anarchists suspicious of formal organizations. The idea of the general strike had resurfaced with the Chicago anarchists during their fight for the eight-hour workday in 1886. Tragically, the Haymarket bomb and subsequent trial led to the execution of four of them. In 1888, Tortelier was “deeply stirred” by what he perceived as an American general strike movement and became relentless in his calls for “Revolution Through General Strike” wherever he was invited to speak in France. “It is only through the general strike,” he’d thunder, “that the worker will create a new society, in which we will no longer find tyrants.”7 On March 16, he addressed a large number of Italian and French anarchists during their commemoration of the Paris Commune in New York’s Webster Hall. One reporter was impressed by the thirty-seven-year-old Frenchman:

His readiness in defense of his views in every phase, moral and economic, with his abundant quotations from the scientists, would astonish our college professors, albeit he is a working cabinetmaker.8

The German anarchist John Most, possibly the most notorious revolutionist in the United States, joined Tortelier on stage for a quick speech in English. Unfortunately, no money was raised.9 A few days later, he gave another lecture just for French-speaking radicals in Frank’s Hall on West Houston Street. Some days later, he traveled to Paterson, New Jersey, to address mostly silk weavers at an international Commune event with speeches in German and English.10 Louis Goaziou had invited Tortelier to give lectures at various locations throughout the coal fields. Since Tortelier did not speak English, the anarchist editor offered to accompany him along the difficult terrain once he got there. Both men hoped to distribute pamphlets and recruit new subscribers.

Tortelier arrived in Hastings on March 31, where he met Goaziou and gave a lecture at the editorial office to about twenty French and Belgian miners. He learned that the men had been on strike, but they still found some pennies to spend on radical pamphlets and travel expenses for their speaking guest. The evening closed with the singing of revolutionary songs. The next day, they made their way to Houtzdale, about twenty-seven miles to the northeast, where a meeting was planned. Bad weather made it difficult for some miners to attend, but those present were eager to buy pamphlets and help out with travel costs. The following day, they traveled twelve miles north to the coal camp of Ashcroft, located just north of Philipsburg. Such isolated coal camps were common and were constructed in the valleys near the layered deposits, permitting a near-horizontal shaft and galleries for easy extraction.

Again, spring rains had turned some roads into mud. Much delayed, they reached the home of Joseph Lannoy, a French miner who immigrated in 1888 and now served as an agent for Le Réveil des Mineurs. Another comrade went out to summon about forty miners to a meeting hall where Tortelier was to speak. They stayed with Lannoy until Saturday, April 4, when Goaziou and Tortelier headed back to Houtzdale. Both men must have made an impression because the miners who gathered for a lecture promptly decided to form a revolutionary group. Two days later, the men traveled south to Lilly, where they met up with fellow radical Henri Haubry, who opened his house to ten more miners to attend Tortelier’s lecture.

Marie Haubry, Henri’s spouse, was also an anarchist activist in her own right. She urged women to hasten the hour of revolution by providing their children with an appropriate revolutionary education.11 Undoubtedly, there were more women like her who gave what little time they had to the cause of social revolution but left no records for historians. Nevertheless, the community of radical miners was male-dominated. In 1892, one French woman from Ashcroft complained to Le Réveil des Mineurs that the men did not permit women to play a role in running the group’s meetings. This was wrong and misguided, responded editor Goaziou, because “women educate children, and the more they know our ideas the better they will raise them.” He added a needed reminder to the male comrades: “Let us learn to see women as our equals and not as our slaves. If we don't give women freedom, we don't deserve to be free ourselves.”12

On Tuesday, April 7, Tortelier and Goaziou set out to visit mining towns further west in Allegheny and Washington counties, south of Pittsburgh. One historian estimates that between three and four thousand French-speaking miners resided in the greater Pittsburgh region.13 Along the way, they stopped at Jeannette, a glassmaking center sixty-four miles west of Lilly. The town had only been incorporated two years earlier but had grown quickly to over 3,300 residents, a majority skilled Belgian and French glassworkers. Since the glassworkers worked in seven-hour shifts, only a small number would be able to attend a lecture. Tortelier decided to travel on but return to Jeannette the next Saturday when a full house could be expected. In the meantime, he gave a lecture to thirty people in Federal where Goaziou’s paper had an agent. The next stop was McDonald, another town whose population exploded in the last decade to stand at 1,700 residents. It was located along a small river called Robinson Run, together with several other coal towns such as Willow Grove, Noblestown, Sturgeon, and Midway, all home to a substantial number of francophone miners. Comrades in McDonald advertised the lecture in advance and procured a large hall, which filled to 250 people when Tortelier arrived.

Tortelier was not the first voice of anarchism these miners heard. Since the mid-1880s, small groups of revolutionaries had formed among the miners in dozens of coal towns across western Pennsylvania and the Midwest. In Sturgeon, for example, a town where Goaziou used to live, there existed a communist-anarchist group for years. These affinity groups had a hard time sustaining an active network not only because of the terrain but also because miners were constantly on the move. However, the historian Michel Cordillot points out that the constant moving tended to strengthen personal contacts and the exchange of information.14 Things improved with the launch of Le Réveil des Masses (The Awakening of the Masses) in January 1888, the first periodical centered on the radical francophone miners, which was succeeded by Le Réveil des Mineurs in November 1890.

On Saturday, April 11, the two travelers were back in Jeannette, where Tortelier gave a lecture attended not by miners but by the 120 members of the secret Lafayette Circle of glassworkers. Most of them were socialists affiliated with the Knights of Labor Local Assembly 300. These workers earned more in one week than a miner in a month and tended to see anarchists as impractical agitators. They believed that “anarchists only know how to talk about destroying the current system of exploitation,” remembered Goaziou, “but have nothing to put in its place.” While there were some interruptions, Tortelier managed to deliver a solid argument that, by the end of the evening, received applause from the hall. The glassworkers certainly understood the meaning of solidarity and were moved by the plight of the miners. “They know that one cannot be truly happy as long as others suffer,” Goaziou wrote, “and that they should not stay out of the movement just because they earn a good living [...] We found comrades in Jeannette who were, so to speak, anarchists without knowing it.” The glassworkers ended up defraying hotel and other travel expenses.15

On April 13, Goaziou and Tortelier headed twenty miles west to the Monongahela River, where several mining towns were located. In Hope Church, just south of the giant Carnegie steel works at Homestead, Tortelier gave a lecture to sixty people. They also visited the home of Étienne Bartelot, an anarchist activist and agent for Le Réveil. The next day, they took a train along the river to West Elizabeth. From there, they walked to the next coal town called Calamity, where radical miners from neighboring towns gathered to hear Tortelier. However, he fell ill and was forced to rest for several days at the home of another anarchist activist and agent, Clément Valtille. Tortelier decided to return to New York on April 17, where he remained for another two weeks before sailing for France. Goaziou, who returned to Hastings, acknowledged how beneficial it was for an editor of a miners’ paper to travel the region:

For our part, we are pleased with our trip, having had the pleasure of seeing several old friends and also meeting some good companions with whom we had long corresponded.

He could also be happy about the $75 collected from the comrades during this tour. After paying expenses, $21 remained, which was donated to Tortelier’s family in France.16

In the wake of Tortelier’s speaking tour, several radical groups with names like “Les Gueux” (The Beggars) and “La Revanche des Mineurs” (The Revenge of the Miners) were formed among the Belgian and French militant coal miners. Historian Ronald Creagh noted, “It is very likely that the birth of many of these groups is due to the militant efforts of a leader from France, the cabinetmaker Joseph Tortelier.” Tortelier undoubtedly convinced many in his audience of the value of anarcho-syndicalism and the general strike, the topics for which he was most known. Militant miners recognized the value of unions but, like many anarchists, criticized trade unions for being reformist. However, thanks to Tortelier’s arguments, they never broke with unionism. After the Haymarket affair, many miners shifted their membership from the Knights of Labor to the United Mine Workers of America. Within this new union, the francophone miners acted as defenders of ethnic minorities by demanding from the union leaders that they use interpreters, but this was rejected. According to historian Ronald Creagh, “they then set up ‘free unions’ that would challenge the leaders at national congresses.”17

Joseph Tortelier remained active as an anarchist and syndicalist until his death on December 11, 1925. Louis Goaziou continued to serve as one of the key figures in French-speaking radicalism in the United States. He became a member of the Industrial Workers of the World, then a socialist, and by the thirties, he was an enthusiastic supporter of Franklin Roosevelt. He died in Charleroi, PA on March 31, 1937.

The description of Tortelier’s tour comes from “L’Anarchie en Pennsylvanie,” Le Réveil des Mineurs, May 2, 1891, p.1. For a map, go to my website and click on “Anarchist Places in the Americas” map.

Reports of the Inspector of Coal Mines of the Anthracite and Bituminous Coal Regions of Pennsylvania for the Year 1891 (Harrisburg, 1892), 424.

“La Situation a Hastings,” Le Réveil des Mineurs, January 31, 1891.

Reports of the Inspector of Coal Mines, 425-6.

Haubry, “Correspondances,” Le Réveil des Mineurs, January 31, 1891.

Charles Malato quoted in https://maitron.fr/spip.php?article155619

Quoted in Kenyon Zimmer, “Haymarket and the Rise of Syndicalism,” In: The Palgrave Handbook of Anarchism, edited by Carl Levy and Matthew Adams (Palgrave Macmillan, 2019), Paul Mason, Live Working Or Die Fighting: How the Working Class Went Global (Haymarket Books, 2010), 119.

Twentieth Century (New York), March 19, 1891, p.14.

Freiheit (New York), March 21, 1891.

Ibid.

Michel Cordillon, ed. La Sociale en Amérique: Dictionnaire biographique du mouvement social francophone aux États-Unis (1848-1922) (Paris: Les Éditions de l’Atelier, 2002), 228.

“Avis,” Le Réveil des Mineurs, February 20, 1892, p.4.

Michel Cordillot, Révolutionnaires du Nouveau Monde: Une brève histoire du mouvement socialiste francophone aux États-Unis (1885-1922) (Lux Éditeurs, 2009), 26.

Cordillot, Révolutionnaires du Nouveau Monde, 32.

“L’Anarchie en Pennsylvanie,” Le Réveil des Mineurs (Hastings, PA), May 2, 1891.

Ibid.

Ronald Creagh, Nos Cousins d’Amérique: Histoire des Français aux États-Unis (Paris: Éditions Payot, 1988), 380-1.

Thank you for sharing this beautiful history! I was unaware of a lot of this and I’m excited to look into it more.