Go down the Bowery any Sunday evening, and in stuffy, ill-smelling, crowded rooms you will find Germans and Bohemians and Hungarians advocating the overthrow of the existing social conditions, and their sentiments wildly applauded by hundreds of foreign workmen.1

These were the words of Hjalmar Boyesen, a Norwegian-American language professor at Columbia. Boyesen was among many in academic and political circles at the time urgently advocating for immigration restrictions. His concern reflected two common assumptions of the era: anarchism was a dangerous foreign import, and its proponents lurked in America’s urban underbelly, plotting revolution in hidden corners.

There was some truth to this. During the Gilded Age, many anarchists were indeed urban dwellers, and a significant number were foreign-born or the children of immigrants.

But Boyesen and his peers might have been surprised to learn that anarchism found fertile ground far beyond the tenements of industrial cities. It resonated with thousands of native-born Americans with names like Byington, Fox, Walker, Holmes, or Tucker—people who carried the torch of radical thought in places like Kansas, Tennessee, and Oregon.

Before we go any further, let’s dispense with the tired trope of the crazed anarchist bomb-thrower. While this image has a storied and fascinating history in the United States—one we might revisit in another piece—it’s also a misleading stereotype. Most anarchists of the period were neither crazed nor bomb-throwers, and many openly criticized the few who were.

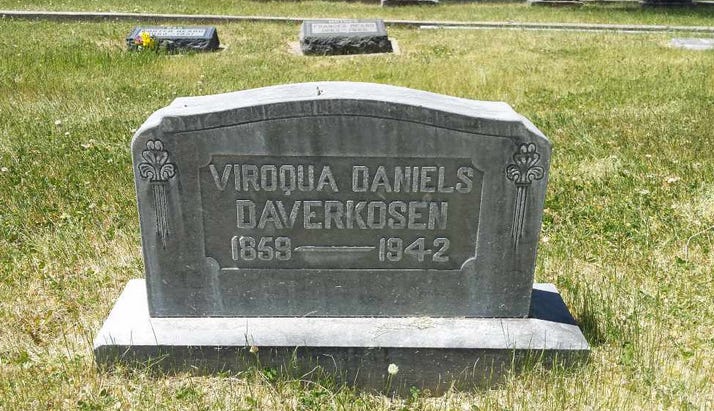

Which brings us to Viroqua Daniels.

Her name might not be widely recognized today, but around the turn of the 20th century, Daniels was a fiercely independent anarchist-communist. With a razor-sharp pen, she challenged the deeply ingrained social norms of her time, slicing through the layers of reverence and authority that shaped American life.

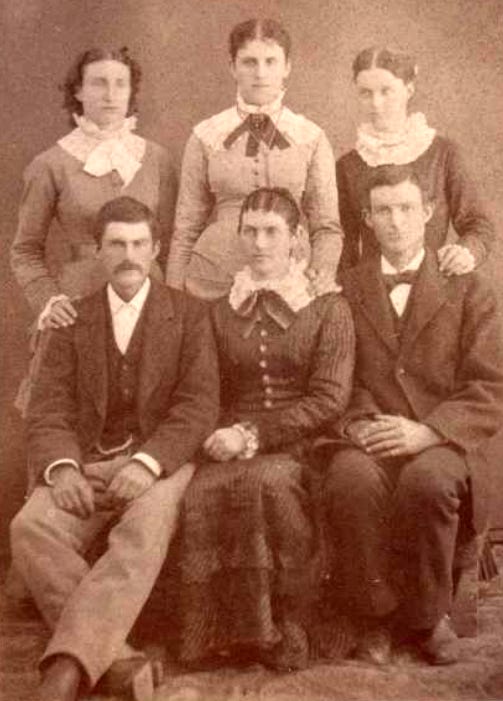

Born in December 1859, Viroqua was the third child of Sylvester and Mary Daniels, farmers in Cedar County, Iowa. This area in eastern Iowa was not only a station on the Underground Railroad but also a place where extreme weather shaped the lives of its residents. Just six months after her birth, a massive tornado tore through Cedar County, killing over 100 people and causing $1 million in damage. The Daniels farm, however, was spared.2

When the Civil War broke out, Viroqua’s father, Sylvester, enlisted in a Union infantry regiment. He served as a musician, playing the fife, bugle, and fiddle, and kept a diary detailing his wartime experiences. Sylvester saw action at major battles, including Vicksburg and the siege of Atlanta in July 1864.3 After the war ended, he returned to Iowa, where his farm’s real estate value tripled between 1860 and 1870.4

By the time Viroqua was 14, Sylvester was considering a fresh start. In 1874, he embarked on a solo journey of over 1,700 miles to northern California, scouting for land and a more forgiving climate than the harsh plains of Iowa. His travels took him through Honey Lake Valley in Lassen County, near the Nevada border, and eventually to Surprise Valley in Modoc County. There, he found what he was looking for and purchased land.5

Two years later, in December 1875, the Daniels family—Viroqua now 16—joined him in their new home. Lake City, their address in Surprise Valley, was even more remote than Cedar County had been. As Sylvester wrote to a local newspaper, “We are a great way from the world, being nearly 200 miles from Reno, the nearest railroad station.” Despite the isolation, he observed that local farmers were prospering and “making good homes,” though “all news is old when it gets to us.”6

At nineteen, Viroqua Daniels suffered a life-altering accident when she hit her head against a wagon wheel. The injury caused chronic pain and sickness that plagued her for the rest of her life. Historian Robert Helms notes that her condition often forced her into a quiet and secluded existence, making public speaking or extensive travel impossible. Instead, reading and writing became her most vital outlets.7

Her health challenges also prompted her to reflect critically on conventional medical practices, including vaccination. Her critiques, while reflecting her anarchist skepticism of hierarchical institutions, might strike modern readers as extreme. In one article, she championed hydropathy and dietary changes as cures for disease and denounced reliance on doctors or pharmaceuticals. For Daniels, medicine—like politics—was an area where expert control over individual lives was suspect.

Little is known about her life during her twenties, but it’s clear she developed a growing interest in social and political issues. At some point, she left her parents’ farm and began boarding with a neighboring farmer who employed a young farmhand named Albert Pruett.8 The exact nature of her relationship with Pruett remains unclear, but their proximity suggests the possibility of a personal connection. Did she leave home due to a falling out with her family? Without solid evidence, this remains speculation. Years later, however, Daniels openly critiqued the family as an institution, writing, “What there is that is desirable about the family institution, I do not see,” and, “The distinctive ideal of the family, good fellowship, is more easily secured elsewhere.” Her writings hint at an ideological, or perhaps personal, rift with her devoutly religious family, as Daniels became increasingly vocal in her opposition to religion and piety.9

It is likely that Daniels identified as an atheist before she embraced anarchism. How she first encountered anarchist thought remains uncertain, but one plausible scenario is that she moved to the San Francisco Bay Area in the late 1880s, where she may have met radicals and labor activists. By 1900, she was living in Berkeley with Sigismund Danielewicz, a Jewish anarchist and labor organizer. Danielewicz was a rare voice among white radicals of the time who opposed the rampant anti-Chinese violence in the Western labor movement. He was also an important link in a network of activist editors—figures like Albert Parsons and Dyer Lum—dedicated to bringing revolutionary anarchism to English-speaking audiences, particularly on the West Coast.

Daniels soon became part of this anarchist press network, contributing essays to various West Coast publications. Among them were short-lived but significant periodicals like The Beacon, Firebrand, Free Society, The Agitator, The Demonstrator, and Why?. To outsiders, the proliferation of these ephemeral titles might suggest the anarchist movement’s fragmented or ineffectual nature. But a closer look reveals that these publications were part of a coordinated effort. Editors and contributors often relaunched their papers under new names, maintaining a nearly uninterrupted stream of anarchist perspectives, commentary, and poetry for nearly two decades, from the late 1880s until World War I.

Starting in 1895, Viroqua Daniels emerged as a significant voice in the anarchist movement, standing out among a diverse group of male and female writers capable of tackling a wide range of topics in English. Publications like Firebrand and Free Society provided the perfect platforms for Daniels and others to explore the many facets of anarchist-communism. These newspapers delved into everything from economics and labor politics to social and philosophical issues such as free love, sexuality, marriage, feminism, and hygiene.

“By combining the economic and political arguments of anarchist communism with the social and cultural ideas of free love,” historian Jessica Moran has observed, “Firebrand and its contributors consciously developed an anarchism that appealed to both immigrant and native-born Americans.”10 Viroqua Daniels was not only part of this intellectual network but played a creative role in shaping the evolution of anarchism into the 20th century.

Daniels’ writings exemplified the sharp rhetorical style characteristic of late 19th-century anarchist discourse, yet her voice stood out even among her peers. Her tone was often scathing and sarcastic, laced with irony and rhetorical questions. She had a gift for mockery and provocation, but her arguments were always incisive and delivered with remarkable brevity. The editors of Firebrand once called her a “first-class writer,” noting that she managed to convey more in a short article than Marx could in his Capital. A year later, responding to a reader’s inquiry, the editors praised her as “an earnest woman, a vigorous thinker, a clear writer, and the especial pride of the movement of the west.”11

Daniels had a keen grasp of both the philosophical and practical dimensions of anarchist-communism. She was particularly eloquent on the emptiness and alienation of modern capitalist society. “The modern commercial mill has ground the last spark of obtainable profit out of the living masses,” she wrote, “and is at this moment run by the fictions of presumable profits of the masses yet to come. It has worked everything in sight, and nearly all speculative futures. Can we keep on forever in the old way?”12

To Daniels, the ethics and politics of anarchist-communism offered a solution to this endless cycle of exploitation and greed. She outlined its vision with clarity and conviction:

Do to all others as you would be done by; that is Anarchist-Communism, and when that ideal is lived there will be in the associations of men no religions or political rulers to pry, prod or prey; no commercial pirates before whom the masses will tremble at the order, 'Pass over our profits'; no employers, no bosses, no hirelings, no sex domination; there will be voluntary exchange and donations of favors—'Each for all and all for each.'13

For Daniels, economics and politics were inseparable, as she believed “Despotism is irrevocably united with ownership.”14 She often critiqued the myth of democracy under capitalism, rejecting the idea that anyone could rise to wealth and power in a fundamentally unequal system. This myth, she argued, blinded people to the systemic inequalities underpinning society.

Instead, Daniels envisioned a world without money, profit, or commerce. Goods and services would be exchanged equitably, cooperation would replace competition, and individuals would choose work suited to their abilities, collaborating with those they found agreeable. Her vision rejected hierarchy in all its forms, offering an alternative where harmony and mutual aid formed the basis of human relationships.

In her writings, Viroqua Daniels extended her critique of oppression beyond traditional targets like the state and church to include the family and commerce. She believed that even intimate social structures could perpetuate inequality and restrict personal freedom. On marriage, she wrote:

The law by causing the wife to be dependent on the husband for even the common necessaries of life, subjects her to his will, just as truly as the day laborer is subject to his master (employer). What can be worse than sex slavery?15

As a woman in the anarchist movement, Daniels held a nuanced view of the suffrage movement. While she considered it a flawed solution, she acknowledged its value in challenging women’s perceived inferiority:

In short, the agitation is beneficial when it increases freedom of thought and action. As a panacea for the aggregation of ills of our distracted society—failure, is branded on all sides of it, for suffrage, male or female, is merely a bait fastened to the political machinery to coax the populace to tolerate the government trap.16

At the core of Daniels’ critique was a rejection of servility and hierarchical authority. She argued that submission to incompetent leaders only perpetuated suffering:

Servility and submissive slavery show the will to be in subjection. We bow and smirk before our divinely appointed but incompetent overseers—and starve! The starving proves the incompetency.17

Daniels contended that no individual or institution had the right to control others, yet power consistently imposed itself without justification. Liberation, she insisted, could only come through self-emancipation:

We must free ourselves; no other can tear the slave bandage from our brow. Our wants are not gratified on account of slavish submission to the presumptuous regulations of priest, politician, plutocrat; on account of suspicion of one another.18

Her vision was optimistic. Daniels believed that in the absence of external constraints, individuals would naturally develop progressive and cooperative qualities. Like many of her peers writing for Firebrand and Free Society, Daniels sought to balance individual freedom with the necessity of mutual aid and communal support.

In September 1897, the editors of Firebrand were arrested under the Comstock Act for sending “obscene materials” through the mail—one of the offending pieces was a poem by Walt Whitman. Undeterred, they launched a new newspaper, Free Society, in San Francisco, and Daniels continued to contribute to this successor publication.

Around 1900, Daniels met and married Richard Daverkosen, a German-American house painter and former soldier. The couple welcomed their son, Herman Hubert, in Los Angeles in September 1901. Despite her new responsibilities, Daniels remained active in the movement, publishing articles and poems in Emma Goldman’s Mother Earth and Seattle’s anarchist paper Why? until the outbreak of World War I.

After Richard’s death in 1927, Daniels lived with her son until her passing in 1942.

In future newsletters, I will share some of Viroqua Daniels’ poems.

“Unrestricted Immgration,” New York Times, March 20, 1888, p.8.

Cedar Falls Gazette, June 8, 1860.

Report of the Adjutant General and Acting Quartermaster General of Iowa (Des Moines, January 1, 1863), Vol. 1, p.418; Alexander G.. Downing's Civil War Diary (United States: Historical Department of Iowa, 1916), p.133, 304; James A. Davis, “’Old 100th’: Militarization, and Nostalgia during the American Civil War,” in: Sacred and Secular Intersections in Music of the Long Nineteenth Century: Church, Stage, and Concert Hall, edited by Eftychia Papanikolaou, Markus Rathey (Lexington Books, 2022), p. 302.

US Census of 1860 and 1870.

Frontier Times : The 1874–1875 Journals of Sylvester Daniels, edited by Tim Purdy (Van Nuys, CA, 1985).

“Agricultural Notes,” The Pacific Rural Press (San Francisco), January 26, 1878.

Helms, “Daniels, Viroqua,” in: The New Encyclopedia of Unbelief, edited by Tom Flynn (Prometheus Books, 2007): 224-5.

US Census of 1880.

Daniels, “Opportunity,” Free Society (San Francisco), July 15, 1900.

Moran, “The Firebrand and the Forging of a New Anarchism: Anarchist Communism and Free Love,” The Anarchist Library (Fall 2004): https://theanarchistlibrary.org/library/jessica-moran-the-firebrand-and-the-forging-of-a-new-anarchism-anarchist-communism-and-free-lov

Letterbox in Firebrand, March 31, 1895 and June 7, 1896.

Daniels, “Questions and Answers,” Firebrand, June 2, 1895.

Daniels, “Anarchist-Communism,” Firebrand, August 18, 1895.

Daniels, “Symposium on Anarchist-Communism,” Firebrand, September 15, 1895.

Daniels, “The Marriage Institution,” Firebrand, June 9, 1895.

Daniels, “Questions and Answers,” Firebrand, June 2, 1895.

Daniels, “Independence-or Semi-Slavery. Which?” Firebrand, January 27, 1895.

Daniels, “Opportunity,” Free Society, July 15, 1900.

Thank you for this post! As an American of anarchist sympathies but not well versed in its history, the only anarchist woman I've heard of is Emma Goldman. I suspect that's common for many Americans with some education. I was excited reading about Daniels and the many organizations and people she worked with. I had no idea that there was so much organized activity at the time.

Thanks. A fascinating life. A "native born" anarcho-communist who came by it through life experiences!