In an age of rising authoritarianism, moral delusion, and superstition, holding on to optimism—let alone idealism—about humanity can feel like a losing battle. To resist is to swim against the tide and deny demands for conformity. Silence is submission. This kind of dissent has a long and storied tradition. History offers examples of contrarians who, in times of great upheaval like the 1930s, chose to shout into the wind rather than watch the masses march blindly toward disaster.

One such voice was Anton Levien Constandse (1899-1985), one of the fiercest critics of religious and political dogma of the Dutch libertarian left in the interwar years. From the moment he embraced anarchism in 1918, he waged an unrelenting campaign against organized religion, militarism, and later, Cold War politics. He published dozens of pamphlets that took aim at the pillars of institutional authority. In his later years, he added sexual reform to his causes.

While several Dutch biographies have explored his life, none exist in English.1 In this brief sketch, we will only highlight his attempts to come to terms with mass politics and absolutist thinking during the harrowing years of 1933 and 1934.

Then in his thirties, Constandse was a mild-mannered anarchist and freethinker who embraced a simple life. He felt far more at ease delivering lectures than manning barricades or defending picket lines. As a young man, he had joined a teetotalers' association and soon began to question the tenets of Christianity, eventually abandoning the idea of God altogether. Over time, he sharpened his arguments in defense of atheism and anarchism—values he saw as enlightened—and earned a reputation as a formidable debater.

Though leftist parties and a labor movement existed, Dutch society in the 1920s and 1930s remained deeply conservative, anchored in tradition, law and order, and a strict sense of propriety. The celebrated Dutch writer Simon Vestdijk dubbed this cultural rigidity fatsoensrakkerij, or “decency policing.” Most citizens accepted the moral supremacy of Protestant ethics without question, along with the virtues of frugality and social stability. These ideals were embodied by Hendrik Colijn, the stern minister-president of the 1930s and a leading figure in the Anti-Revolutionary Party—one of the country's oldest parties, originally founded to resist the ideas of the French Revolution.

Like much of the industrialized world, the Netherlands was hit hard by the Great Depression—or, as Constandse described it, “the collapse of capitalism as we had known it until then.” Unemployment soared from 150,000 in 1930 to 600,000 by 1935, in a country of just eight million. The Colijn administration offered only modest support to the jobless and forbade them from earning anything “on the side.” As in other nations, this climate of hardship and disillusionment fueled the appeal of extra-parliamentary political movements—both Communist and fascist—that promised radical change.

Troubling news poured in from abroad. In January 1933, Hitler came to power in neighboring Germany and quickly set about consolidating a dictatorship. The Nazi regime escalated its persecution of Jews and leftist dissidents. In Asia, Japan had invaded Manchuria in 1931 and set up a puppet state, while in the Soviet Union, Stalin's police state sentenced hundreds of thousands to death or to the brutal grind of forced labor.

Amid the political and economic turmoil, Constandse threw himself with astonishing energy into defending the values of anti-authoritarian politics, freethought, and humanism. When anticlerical commentary in the leftist press prompted Justice Minister Jan Donner to introduce an anti-blasphemy bill—passed in 1932—Constandse was among its fiercest opponents. One of his pamphlets was confiscated, and he later testified at the trial of a peddler who had sold copies of it (the peddler was acquitted).2

Undeterred, Constandse crisscrossed the country—mostly by train, but sometimes by bicycle, pedaling through the flat landscapes of Drenthe and Friesland—giving lectures and engaging in debates at a breathtaking pace. In just one month—October 1933—he delivered nine lectures in six cities, speaking on topics as varied as anarchism, fascism, Kant’s philosophy, and the Reichstag Fire. These events were organized by a range of groups he belonged to or collaborated with, including De Dageraad (Dawn), the leading freethinkers' association in the Netherlands; the Vrije Socialisten Vereniging (Association of Free Socialists); and the International Anti-Militarist Association (IAMV), founded by the celebrated Dutch anarchist Ferdinand Domela Nieuwenhuis.

By 1934, Constandse was convinced he was witnessing the “victory of fascism and the increase in the suppression of freedom of expression, the assault on the free intellect, the regression of society into a culturally barren herd mentality.”3 What does this say about our long-held assumptions? he asked. Are there illusions we must abandon? Which ideals remain worth holding on to?

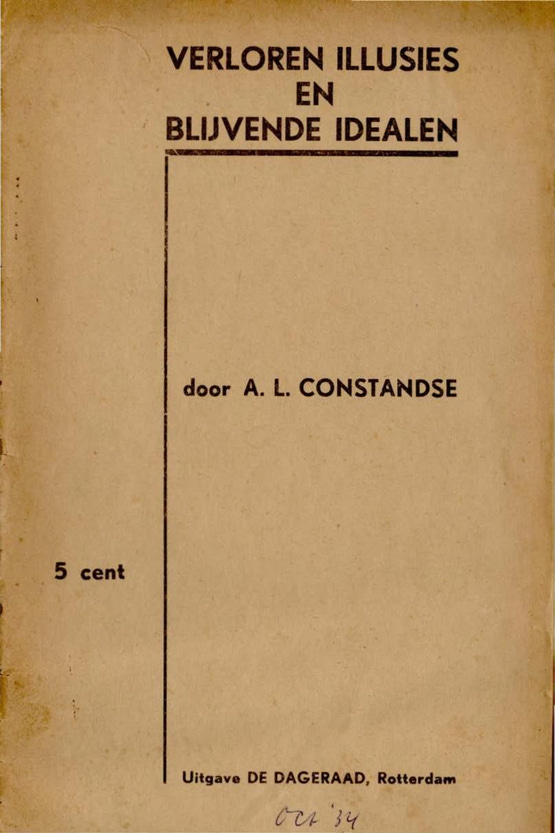

In October 1934, he tried to answer those questions in a pamphlet titled Verloren Illusies en Blijvende Idealen (“Lost Illusions and Enduring Ideals”).

One such illusion, in Constandse’s view, was the belief that the “spirit of the masses” could be steered toward mutual aid and rational cooperation—especially in times of economic crisis. “It becomes impossible to convince everyone of a shared interest,” he wrote (p.3) For much of his life, he had believed that traditional society could be transformed into a decentralized, bottom-up federation of communities through reasoned dialogue. But this now seemed out of reach. Societies, he concluded, had not emerged from solidarity or reason, but from necessity, self-interest, and conflict. The masses, he observed, could all too easily be swayed by irrational appeals and swept into a dangerous herd mentality.

This realization led Constandse to abandon one of the foundational beliefs of classical anarchism: the idea that human beings are inherently good. With it, he also discarded the optimistic notion that humanity was steadily advancing in moral development. “Would humanity around 1900 in Western Europe have committed the atrocities and cruelties so universally as it did in 1933?” he asked (p.6-7)

Unemployment, poverty, and deprivation brutalize, stoke jealousy, increase hatred, arouse blind instincts devoid of reason, and plunge us into the mad world in which we now struggle to breathe (p.7).

Constandse—who frequently lectured on Kant, Hegel, and Nietzsche—came to recognize that truth was far less essential to human well-being than idealists often claimed. “The majority of people,” he observed, “live quite contentedly without ever delving, searching, or reflecting on philosophical questions, instead existing in illusion and intoxication.” The pursuit of truth, he argued, had always been a privilege—dependent on a degree of social stability and security. Even prosperity, he warned, does not ensure a civilized individual or society. “It is not the case,” he wrote, “that prosperity compels someone to seek truth or beauty” (p.8)

To make his point, he offered a vivid and unsettling example, one still strikingly relevant today:

A brute who improves his lot may only become a greater brute; a power-hungry individual in a high position can become a disaster for humanity. Many profiteers become ostentatious caricatures of civilized beings as newly wealthy bourgeois (p.8).

In the end, Constandse concluded it was futile to expect people, in general, to abandon their religious or political illusions in favor of the harsh, often joyless truth. The human mind, he believed, is a survival mechanism—evolved not to confront reality, but to soften it, to render the unbearable tolerable, and to keep terror at bay.

After this sobering analysis, Constandse draws the reader back from despair with a surprisingly uplifting defense of holding on to ideals in a world dominated by profit and pain. With characteristic economy of language, he offers a striking juxtaposition between illusion and ideal:

An illusion is the belief that something exists. An ideal is the trust in what does not exist. (p.10)

He follows with examples of illusions: belief in a Heavenly Father, in bourgeois democracy’s ability to resist fascism, or in the League of Nations as a guarantor of peace.

In contrast, an ideal, he writes, is:

Knowing how unimaginably harsh life is and still not becoming despondent or pious. Knowing that what we wish for does not exist and perhaps never will, and yet striving for it. An idealist is one who fully understands that there is no culture today and yet remains loyal to it in thought and action. (p.10)

But an ideal is not merely faith in a better future. What defines an idealist who is truly alive, according to Constandse, is self-awareness—the conscious decision to become who one chooses to be. Most people, he argues, “neither wish to know themselves nor others; they act instinctively and rationalize it afterward with the cleverest arguments.” (p.11)

The idealist is compelled to maintain, not his rank, but distance. His pride is in refusing to be used for everything to which the masses lend themselves, refusing to believe everything the multitude adheres to, refusing to be seduced into accepting what they are willing to embrace. If necessary, to have the courage to think, investigate, and speak on his own. (p.11)

Among the enduring ideals worth defending, Constandse singles out freedom of expression. “A cultured people,” he writes, “is one that grows and is educated in reverence for culture, even if it does not itself grasp beauty or sublimity.” Fascism, by contrast, turns “the masses against cultural phenomena they do not understand or know, transforming them into a culture-destroying force” (p.13). He believed that reconciliation between the masses and culture could only occur under improved economic conditions.

He ends his essay on a note of defiant hope:

Thus, we hold on to our social ideal, even if its realization may be distant, and even if the era we face may be difficult, harsh, and perhaps catastrophic; our impatience grows in proportion to the tragedy of existence. (p.14)

Look out for more of Constandse’s writings in upcoming newsletters…

See for instance: Inge Heuff, Het anarchisme van Anton Constandse (Den Haag, 1981); Pieter Maessen, De levensbeschouwing en het anarchisme van Dr. A.L. Constandse (1990); Hans Ramaer, Het individualisme van Anton Constandse (Moerkapelle, 1995); Bert Gasenbeek, Rudolf de Jong, Pieter Edelman, eds, Anton Constandse. Leven tegen de stroom in (Breda, 1999).

"Tweede Godslasteringsproces,” Het Volk: Dagblad voor de Arbeiderspartij (Amsterdam), June 1, 1933, p.3.

Constandse, Verloren Illusies en Blijvende Idealen (Rotterdam, 1934), 3. Translations are my own. Subsequent citations are from this pamphlet.

Thanks for sharing this! This was an interesting read and it was fascinating to learn about Anton Levien Constandse (1899-1985)!

I love this newsletter because it introduces me to anarchist thinkers I’ve never heard of. Thank you! Looking forward to learning more.