Mapping Immigrant Anarchists

If your knowledge of the history of anarchism is only slight or non-existent, don’t blame yourself too much. Anarchism has been misunderstood, marginalized, and criminalized as a philosophy and movement for decades. Luckily, a renaissance of scholarship is underway, slowly pushing back against persistent misconceptions. Early attention to anarchism and its history often came from outsiders who judged it by alien standards. What did these anarchists accomplish? Where are their political organizations, parties, and platforms? Well, now, anarchists never set out to build those things, at least not in a centralized manner or for electoral gain.

Anarchists did build an anti-authoritarian movement culture and practiced their ideals as much as possible. “Without its clublife, press, unions, and culture,” asserted one historian, “the ideology of that movement is unintelligent.”1 Precisely.

We must investigate a social movement like anarchism literally on their turf!

To do this, we must be clear on what to look for in a social landscape. What kind of meeting places can we expect to find in the American cities of the late nineteenth century when immigrant anarchists began to forge their movement distinct from the socialists?

Let’s dwell on one of the distinctions between the socialist and anarchist movements. Unlike anarchists, socialists do not oppose the state; they participate in party politics and electoral campaigning, which provides an outlet for their ideas.

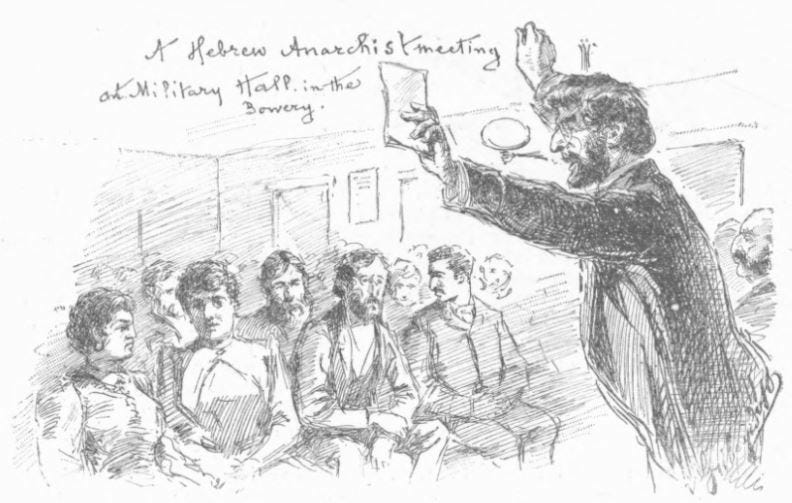

Since anarchists don’t care for party politics and shun bourgeois institutions, their meeting places assume a much more central role in maintaining the movement simply because of their anti-authoritarian philosophy. While anarchists certainly dreamed of a new future society, they were committed to practicing their ideology here and now rather than waiting for electoral victory.

In other words, anarchists may experience their political identity more immediately and spatially than socialists do.

Not that socialists had no associational life—they most certainly did. But they operated on a crucial temporal plane every time election deadlines or office term limits loomed. Achieving political power was primary and recreational life stood in the service of that goal.

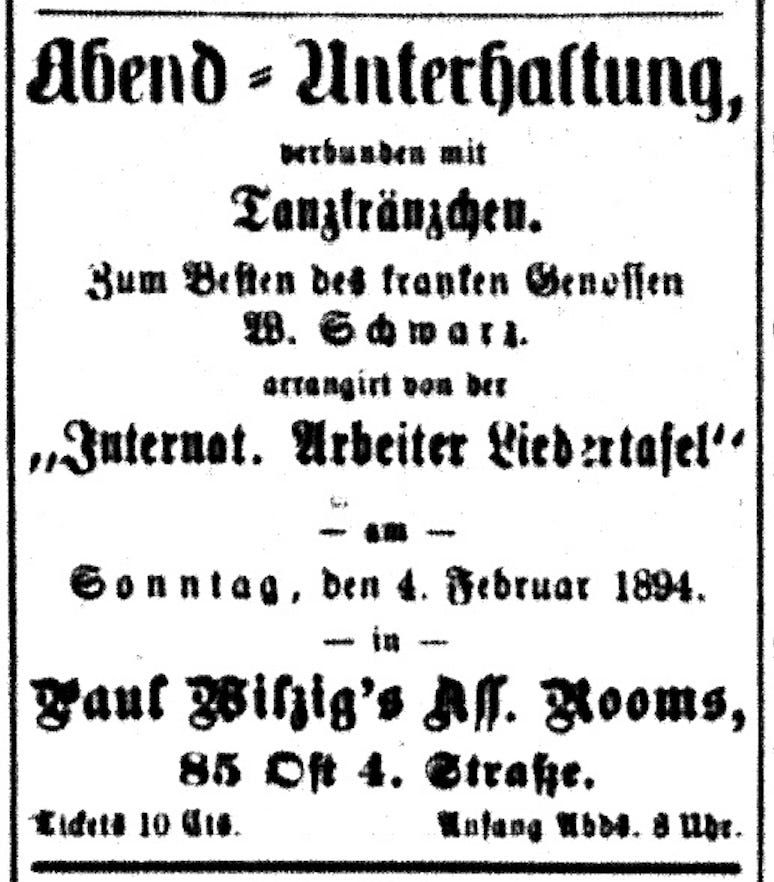

How do these insights help the historian when examining sources left by various immigrant anarchist movements? For one, just because a social movement rejects the traditional infrastructure of party politics does not mean that anarchists are absent from the scene. Their movement existed elsewhere in the landscape. Anarchists also attached far greater meaning to seemingly low-stakes meetings such as backroom lectures or recreational fundraisers. On such occasions, they could practice or prefigure their anarchist philosophy, if only for a few hours before returning to the mainstream of bourgeois capitalism.

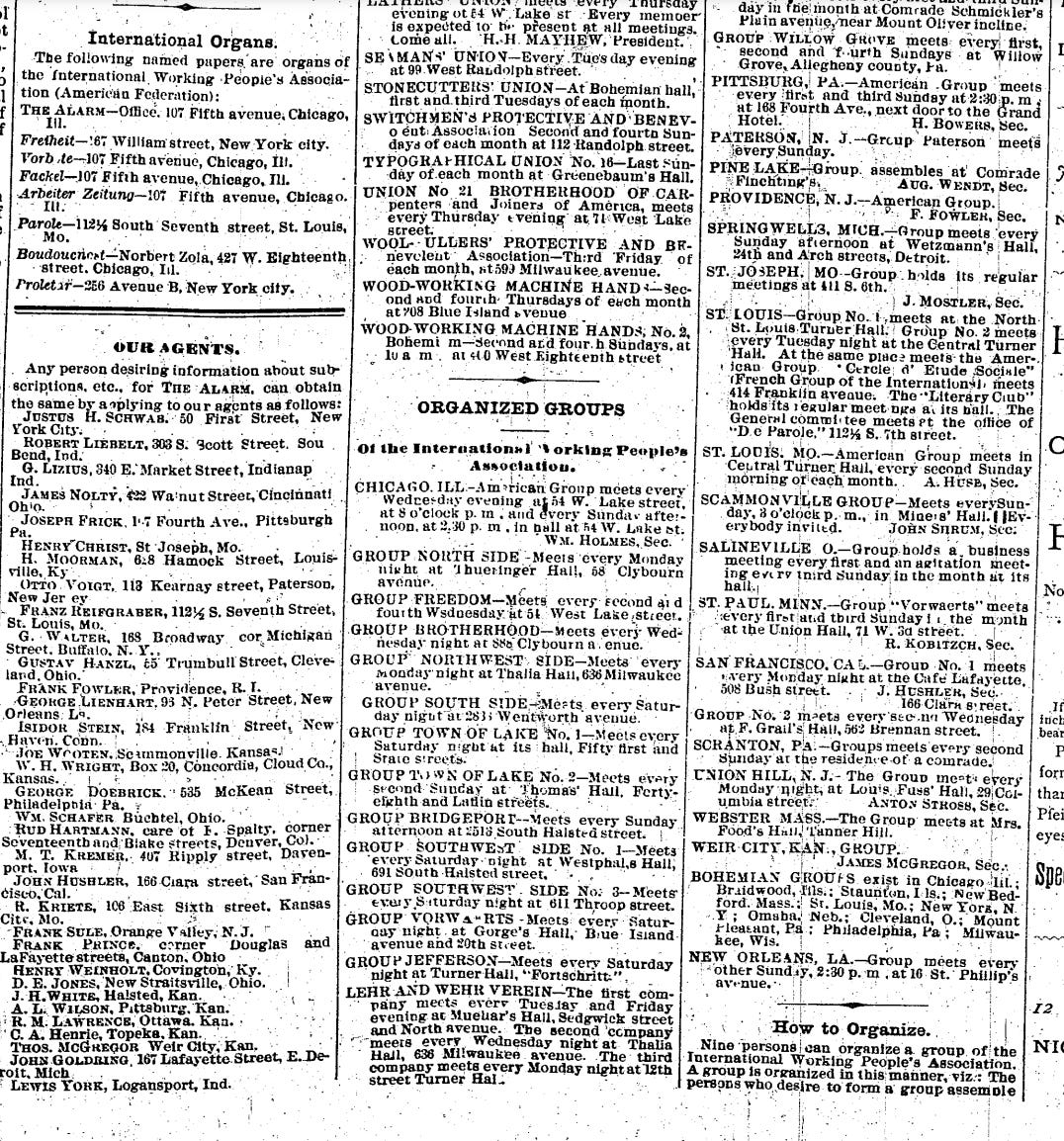

The same logic applies to the meaning of the anarchist press. Without traditional political outlets, anarchists considered their newspapers a public mouthpiece and an internal social medium. The first few pages of a typical movement paper were devoted to articles, opinion pieces, and news. The last page or two, often overlooked, was a jumble of eye-straining announcements and advertisements.

But these announcements are a gold mine for the cartographically-inclined historian.

With periodical consistency, readers are reminded of the richness of their movement and the myriad ways in which they can engage and defy the status quo. Whether one is interested in an agitation club, a reading circle, an amateur theater group, a rifle club, a singing society or band, a lending library, a bookstore, attending a picnic, a fundraiser, an outing, or a commemorative gathering, activities are announced with precise times and locations, and sometimes with directions on how to get there.

This data can be mapped using a mapping platform like Google Maps.

But can we rely on modern house numbers to give us the precise location of a saloon on the East side of Manhattan in 1894? Surely the arrangement and type of dwellings and businesses on East 5th Street look much different today than when pushcarts and carriages rumbled by. Luckily, many large American cities produced detailed survey maps with house numbers and building data for insurance or assessment. The Sanborn Fire Insurance maps are a well-known example. Many such survey maps have been digitized and are accessible online. For example, the 1894 Atlas of the City of New York, published by Bromley, is available through the Library of Congress portal. Bromley published a similar map of Philadelphia in 1895 that is viewable online.

With enough patience and expertise, the historian can now verify the location of meeting places, explore their surroundings, and detect clusters of anarchist activities in specific neighborhoods.

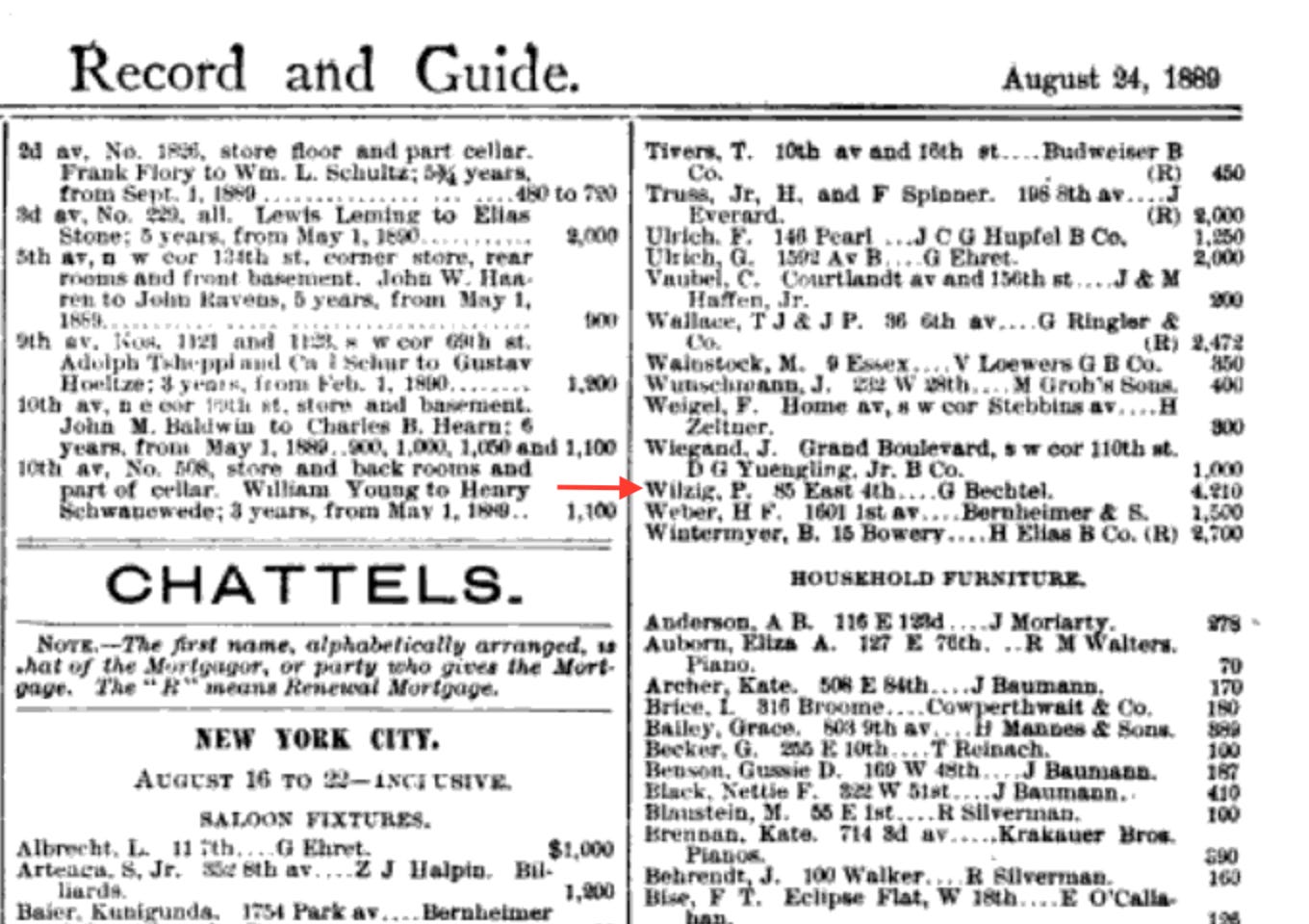

Even more enterprising historians may enlist the help of city directories2, the 1880 and 1900 census records, which list street addresses, or municipal records like New York City’s Real Estate Record and Builders’ Guide.

So what can we learn from mapping the meeting places of the immigrant anarchist movement besides the knowledge that this was a political ideology with an address?

The German anarchists in New York and Philadelphia lived and held meetings amidst their non-anarchist compatriots of Little Germany in the Lower East Side of Manhattan. It is perhaps not so self-evident that German anarchists would settle among their countryfolk, but they did. There was no anarchist neighborhood per se, only clusters of anarchist meeting places sprinkled across the larger German district.

To avoid the impression that the anarchist movement was utterly cut off from the world outside the saloon doors, the historian can supplement this geography of radicalism with other spatial practices such as trolley and ferry lines, urban development projects, police precinct stations, and contemporary descriptions of the metropolis. The proximity of residences to the various meeting places within the neighborhoods shows the movement in a largely walkable terrain.3

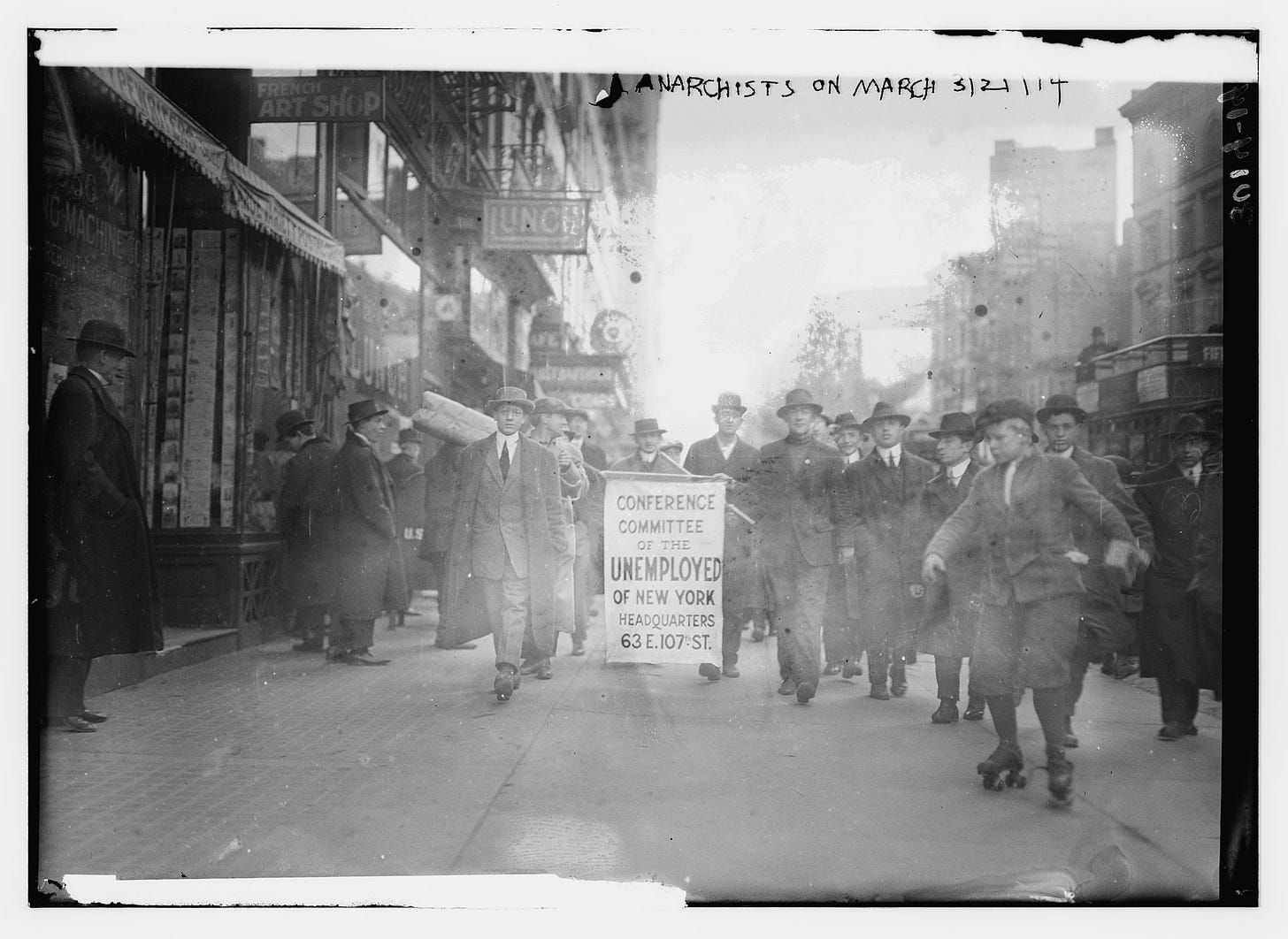

Mapping helps locate the movement with its ideas and culture in the physical environment. Just crafting a space all your own in opposition to the status quo is empowering as much for an individual as for a movement.

Anarchists participated in public demonstrations, labor organizing, cultural and educational activities, and antiwar activism. Still, it is important to remember that finding alternative spaces was a victory of sorts, especially for anarchists. As a French philosopher once said, “Resistance is less about particular acts than about the desire to find a place in a power-geography where space is denied, circumscribed and/or totally administered.”4

Bruce Nelson, Beyond the Martyrs: A Social History of Chicago’s Anarchists, 1870–1900 (New Brunswick, NJ & London: Rutgers University Press, 1988), 240-1.

For more on my writings on social space, see Goyens, “Social Space and the Practice of Anarchist History,” Rethinking History: The Journal of Theory and Practice, 13, 4 (December 2009): 439-457. For access to other writings, go to my Academia page.

Michel de Certeau quoted in Steve Pile and Michel Keith, eds., Geographies of Resistance (London and New York: Routledge, 1997), 15.