Do the poor, the oppressed, and the disfranchised refrain from rebelling against oppressing conditions until they experience the most abject misery? Are poverty and starvation somehow “necessary” for the masses to be moved to liberate themselves?

These questions were on the mind of Claus Timmermann (1866-1941), a German-American anarchist editor and close friend of Emma Goldman. Both lived through the worst economic depression of their lifetime when abject misery was visited upon thousands of workers.

The stock market crash of May 1893 led to a banking crisis and a full-blown depression. Factories closed, homes and farms were foreclosed upon, and countless families were evicted. City parks became refugee camps, and police stations counted more sleeping tramps than officers. Hundreds of thousands of unemployed men and women, Timmermann among them, were left watching the wreckage of capitalism.

New York anarchists, socialists, and trade unionists played a role in exposing the scale of the devastation. In August, labor unions persuaded major newspapers to report the unfolding human crisis. In an article titled “The Army of the Unemployed,” union statistics showed that 36% of New York City union members were out of work as a result of the depression.1

No statistics for nonunion workers or day laborers were available, but the streets, parks, cellars, underpasses, and lodging houses attested to their plight with unavoidable candor.

The anarchists knew the system had failed and were not in the mood to play by its guilty rules. “The bourgeoisie is trembling and fearful of the results of its mismanagement,” wrote Timmermann in September 1893, “Hunger, that terrible scourge of our much-vaunted pseudo-culture, is making itself felt undeniably and unambiguously in an America that is blessed with such enormous wealth.”2 Anarchists like Goldman and Timmermann attempted to organize the unemployed into a public force to change the system. Demand bread, they shouted, and if it’s not given, take it. Both paid the price for that advice by spending time behind bars in 1894—more on that in subsequent posts.

Timmermann realized that the workers’ struggle for liberation should be an ongoing project during good times and bad and cannot be a desperate move in times of distress and deprivation. The experiences of the 1890s stuck with him.

In 1901, he published a realist look at belowground New York that takes the form of a morality tale to address the question we started with. His gritty portrait seems to be set during the depression years after his release in March 1894. The style is reminiscent of Jacob Riis’s famous 1890 investigation of the slums of New York, How The Other Half Lives, and Stephen Crane’s harrowing but unappreciated novella Maggie, A Girl of the Streets, self-published in 1893.

Here is Timmermann’s sketch:

“These stupid workers should starve until their intestines dry out. As long as this hair-brained lot has something to eat or someone throws them a bone, they will not rebel, and there is no hope of overthrowing the existing conditions.”

These were the words of one of my old friends. I, too, once adhered to this view but observing practical life taught me otherwise. As in many other questions, theory and practice are in sharp contrast.

As we were drinking in the famous ‘beer cave,’3 I asked my friend if he would be willing to take a little walk with me to convince him of the error of his views.

“Agreed,” he said, “You arrange everything, and I will pay because I know you suffer from incurable consumption of the wallet.”

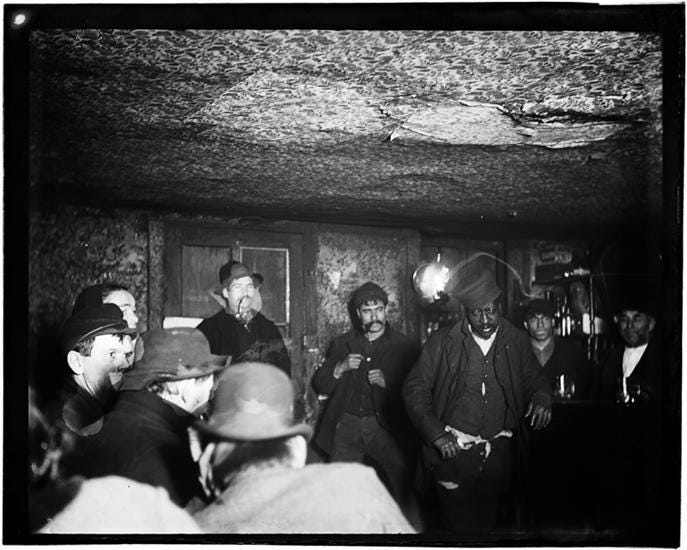

We soon entered a beerhall on the Bowery filled with about a hundred people. With difficulty, we found a place to sit. Signs on the wall announced that for 5 cents, you could get a hamburger steak, 3 eggs in “every style,” sauerkraut, and frankfurters, or something else. This epitomized an Epicurean meal for the poor devils gathered here. Large schooners were poured, squeezing every last nickel from every drinking individual.

When we sat down, someone called to me: “Hello, Claus, to see you here again?” When I answered, my friend asked me, surprised, where I knew him from.

“I know him from prison.”

“So, are there more people like that here?” asked my companion in shock.

“Oh, yeah, there's a whole group over there. This one is just an ordinary burglar who has languished behind bars for many years despite his youth. I once asked him a day before his release whether he wouldn't rather go to work than be locked up again and again. ‘Yes,’ he said sadly, ‘I thought about that, but necessity drove me into this, and I can’t get out. It was different once --- but what do I do now? Poppycock! If I tried and found employment, I would be toiling all day for starvation wages and end up in a hospital. When I’m released soon, before I get downtown, I will have looted so much that I can live comfortably and happily for a few weeks. If one day I’m arrested, then - well, then I'll have to swallow that pill. If all this proves too dangerous, I'll join the militia, where there is also much to do.’ When I told him that he couldn’t join the militia as an ex-convict, he replied with a laugh: ‘Oh, that's all right, I have political pull.’”

“Who are those two raggedy figures at that table over there?” my friend asked.

“Oh, those are two beggars stripped of all character by misery. If one of them enters a place where anarchists gather, he tries to be an anarchist. If he comes into contact with Social Democrats, he supports their ideas. If he visits veterans, he is an old warhorse, and if he meets god-botherers, he overflows with God-fear and piety. These two should become journalists given their current character.”

A particularly shabby man who caught my friend's attention was not far from us. He was covered in dirt and rags, and his facial features spoke of unspeakable misery and depravity. He had just fallen asleep. With a scraggly beard and disheveled appearance, this slumped figure was a disgusting sight. The bouncer quickly approached him and hit him over the knee with a club. He didn't immediately obey the request to get some fresh air but instead stared stupidly and sleepily at his tormentor, who grabbed him by the collar and dragged him outside.

“Oh, I know him; he's a carpenter. Eight years ago, I saw him regularly at meetings, where he listened attentively to the speakers and looked like a worker full of character, striving for freedom. Then came the fall. Frequent unemployment gradually caused him to decline. His family often had to suffer. This led to quarrels, and one day, when he tried to drown his misery in schnapps and his pregnant wife bitterly reproached him for it, he became so angry that he abused her, from which she died soon afterward. You've seen him now. ‘Do you think,’ I added ironically, ‘that the misery has now made this person ripe for social revolution?’”

There was no response.

A few figures representing the lumpenproletariat in every form were sitting at our table. They overflowed with love for the fatherland and reverence for the German Emperor. My companion became irritated by this, intervened in their conversation, and tried to get his point across. But this was easier said than done. ‘What!’ roared one of them; ‘this person is no longer a man but a subject.’ Another shouted: ‘This ass should say such impudent things in the Reichstag where all German states are represented; they’d hang him.’ A third person jumped up and made violent movements, so my Philosopher of Misery found it advisable to get out.

Back on the street, he breathed a sigh of relief and shook his head. “I’ve had enough!” he said.

“Oh, this is just the beginning of our investigation,” I replied. “We were just among the elite of the lumpenproletariat. Now, let's go to a few other places where you will experience even more. Misery will stare you in the face and make you shudder. People? Oh, no, we’re talking about people degenerating into animals - through misery.”

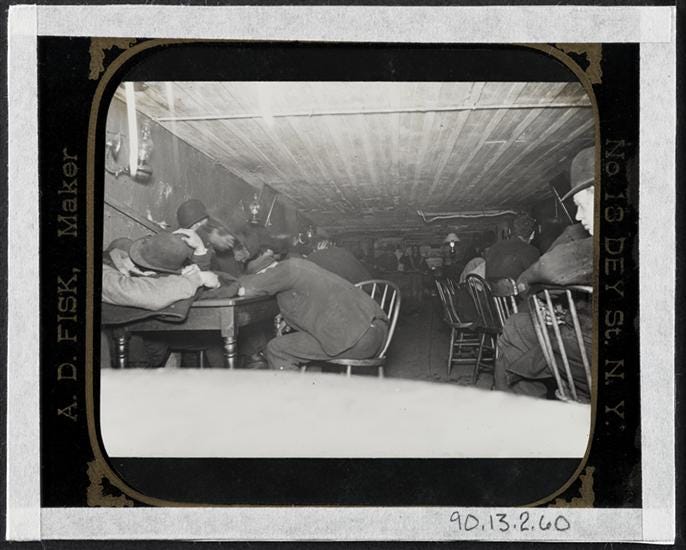

We entered a dive bar, walked through the barroom, and came to a so-called hall. It was full of dirt and polluted air, and the light was only half turned on. In the background, a few heaps of rags scattered on the floor, which, after our eyes got used to the semi-darkness, turned out to be the wrappings of sleeping “guests.” Some of the frequenters of this cave sat on benches, vacantly staring into space, while others frolicked about to practice boxing. The whole thing made such a repulsive and eerie impression that my Worshipper of Misery wanted to leave immediately. But I grabbed his arm and pulled him into the back of the bar.

“Say,” he whispered as he slipped his watch and chain into his trouser pocket at my suggestion, “I think you can get knocked down here for a quarter.”

“Well, possibly for just 10 Cents. The people here have sunk so low that even their professional colleagues avoid them,” I replied.

We sat down at a table. A man was sitting across from us who was reasonably well dressed and wearing blue glasses to make himself unrecognizable. I immediately addressed him as "partner" and offered him a beer. At first, he was suspicious. But when another beer growler was served, I asked him whether this or that guard was still working on the Island.4 I stated other facts proving that I was not a stranger there. He became more talkative and saw me as a fellow professional. I introduced my friend as a “well-bred boy” from Chicago who was recently released from prison and has now moved his operation to New York for good reasons. Dear reader, if only you could have seen his astonished face then. His face turned even more amazed when the stranger moved close to him and asked if he had a “job” for him. The reader can probably imagine what kind of “job” this would be.

Encouraged by my success, I walked up to an old Irishman who looked like a criminal from twenty paces away and whom I greeted as an old acquaintance from Blackwell's Island. Lying through my teeth, I suggested doing a break-in with him that could cost lives but wouldn’t be a problem. But this was too much for my friend, who I had also brought in, and he quickly ran away. In short, he could no longer be persuaded to go to another place with me.

He didn’t lose his watch, chain, or money, but he lost much of his conviction that the greatest misery could drive people to social revolution.

No, it is not misery that will drive the workers to liberation, but rather constant resistance against the complete immiseration of the masses.

I went on alone. A fine, cold rain fell. A poor fellow, shaking with cold, descended the cellar steps where he would spend the night. Someone else crept by, having wandered all night searching for a place to lay his weary head. Women of the street staggered past in dirty outfits.

Finally, daybreak and the giant city awakes with clatter and banging, with greed for life and riches. I walked uptown along Fifth Avenue to Central Park. What a different picture unfolded before my eyes. Here and there, a squirrel peeked out of the bushes, and birds began to chirp. They all had their little nest and their protection—by the state. Along the park, one palace rose next to the other, each more beautiful than the other. I found myself in a completely different world. Beauty, splendor, wealth, and the highest enjoyment of life in every form were at home here. Up here was a world of the most exquisite life of luxury, and down there, another world was sinking in the mire of misery and depravity. And yet, the former is to blame for the latter's downfall. Yes, here feast the guilty people, the true and sole criminals. Here are the causes; over there are only the effects.

The rain had stopped, and the sun rose brightly behind the palaces. Oh, when will the sun finally bring salvation to tormented humanity? Well, that time, too, will come; perhaps it's closer than we think.5

New York Evening World, August 4, 1893.

Die Brandfackel (New York), September 1893, p.1.

This is most likely Justus Schwab’s Liberty Hall saloon on 50 First St.

Blackwell’s Island Penitentiary in New York’s East River.

Timmermann, "Im Elend. Skizzen aus dem Leben von Claus Timmermann,” Freiheit (New York), November 2, 1901.

Sociologists have studied this idea, that deprivation leads to rebellion. First was Stouffer who in a different context looked at morale among soldiers. He found that morale was not the lowest among companies that had the least amount of promotions, but actually the opposite. This lead him to the distinction between absolute deprivation and relative deprivation, whereby companies of soldiers that had more promotions established a higher expectation and so soldiers were less pleased about their individual situation relative to others. Later this was applied directly to political action by Ted Gurr in Why Men Rebel. It is not the absolutely worst off who were prone to revolution, but rather a middling strata who found their current state far from their expectation. I also think this relates to the rise of fascism, but I do not have references for this.

Alas, relative deprivation's causation to social movements has been criticize for numerous issues, in part its psychologizing social phenomenon. See Neff and Tierney 1982.