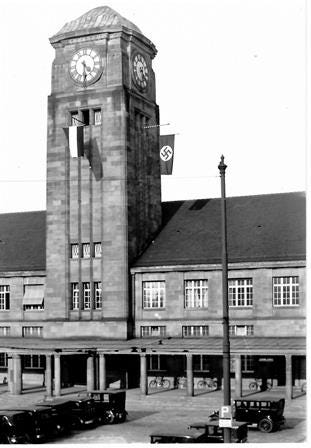

The time at the German border station seemed to take forever. The German officials, only did a quick look into the train compartments and didn't even ask for our passports. Then came the Swiss passport control and after that customs inspection, which […] took more time than we would have liked. The train finally started moving again. We breathed a sigh of relief. We arrived in Basel early in the afternoon.1

Rudolf and Milly Rocker later learned that the Nazis started searching all subsequent trains headed for Switzerland. A day later and this anarchist couple would almost certainly have been arrested and imprisoned as happened to many of their friends. While the crossing was a lucky break, it was just one episode in a harrowing year-long journey at a time when darkness descended over Europe. A sense of loss and despair with an occasional glimmer of hope is palpable in the letters and memoirs that Rudolf Rocker managed to put to paper while trudging across Europe.

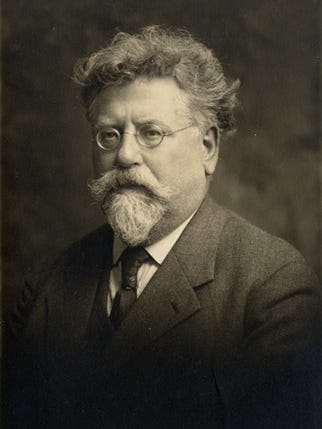

The Rockers were no strangers to the peripatetic life. Rudolf, a gentile born in Mainz, and Milly Witkop, born of Jewish parents in what is today Ukraine, met in London’s East End where both were immersed in the Yiddish-speaking anarchist movement for many years. A son, Fermin, was born there. When the First World War broke out, Rudolf, who opposed the war, was locked up as an enemy alien. In 1918, he returned to his native Germany where the family reunited.

During the 1920s, Rocker became a leading proponent of anarcho-syndicalism, authored many of its manifestoes and pamphlets, and was a key representative at international conferences. He was a prolific and clear-headed writer who despised militarism, nationalism, and the Marxist idea of the dictatorship of the proletariat. He believed that fascism and Communism had toxic DNA in common, namely, the reverence for centralized power. Instead, he advocated anarchist decentralism, direct action, self-management, secular humanism, and international solidarity.

I am an Anarchist not because I believe Anarchism is the final goal, but because there is no such thing as a final goal. —Rudolf Rocker

When they were not traveling in Spain, the United States, or somewhere in Germany, the couple made a modest home for themselves in an apartment in the rather drab Neukölln district on the outskirts of Berlin. Fermin had remained in the United States. The Rockers were well-liked and well-connected within the non-Communist Left in Germany and perhaps in Europe. Two close friends lived nearby: the 74-year-old veteran anarchist activist Wilhelm Werner and the anarchist poet and editor Erich Mühsam.

Besides editor and orator, Rocker was also a writer and scholar. Since the mid-twenties he had been working on a historical study of the concepts of nation and state, but the project had grown into a bulky text on the phenomenon of nationalism—definitely a topic trending at the time. Materials for this study not only came from his impressive library but increasingly from the streets of Berlin. Fights between Nazi thugs and Communist militants were common. In January 1933, fifteen thousand stormtroopers held a rally outside the Communist Party headquarters on Bülowplatz chanting “We shit on the Jew republic!” It became all too obvious that the Berlin police either looked the other way or protected the brownshirts.2 Following some backroom dealings, Hitler was appointed Chancellor on January 30, 1933, prompting thousands to march through the streets holding their requisite torches. But the Nazis were not in total control, and Hitler, despite the viciousness of his followers, needed to maintain a modicum of legality during which he could consolidate power.

Rocker clearly understood the dynamics of an emerging dictatorship based on violence and worship, and this feature of his legacy can hardly be overstated. As an anarchist scholar, he loathed and feared populist demagoguery, worship of any kind, harmonizing of all thought, and the subordination of the individual to a leader, party, or state. His opinion of his compatriots grew bleaker with each passing week. During the early 1930s, his friend the Austrian anarchist historian Max Nettlau, chided him for his harsh pessimistic assessment of the German people. But Rocker was unwavering: “I feel more and more every day,” he wrote in October 1932, “that soon a free person will no longer be able to breathe in this wretched country.” He continued:

We have always had the most miserable bourgeoisie in Germany, and the movement of these spiritual eunuchs toward Hitler is just the latest sign of a lack of character. And Social Democracy? May God have mercy. There never was a more miserable, more repugnant party in the world. No wonder that under such circumstances it should be easy for a rotten nobility to seize power which they lost after losing the war. At our throats today is not an ordinary Reaction, it is the specific Prussian Reaction that, in addition to brutal violence, also uses the smallest chicanery, and whose representatives have an almost sadistic desire to humiliate people as deeply as possible.3

Unlike thousands of ordinary Germans, Rudolf and Milly Rocker understood the danger they were in and feared a European calamity that was sure to follow. The day after Hitler’s appointment, Milly wrote to her brother-in-law, the English anarchist Guy Aldred, that it was clear to her that the Berlin anarchist organizations would be the first to be stamped out.4 Rocker and his friends had already received threatening letters. On February 24, someone told him that the stormtroopers (SA) were convinced (incorrectly) that he had been an English spy during the Great War and that he is considered a “traitor to the fatherland.”5

The prospect of having to leave the city, or even the country, seemed closer than ever. To their great relief, the Rockers still possessed a passport valid for two more years.

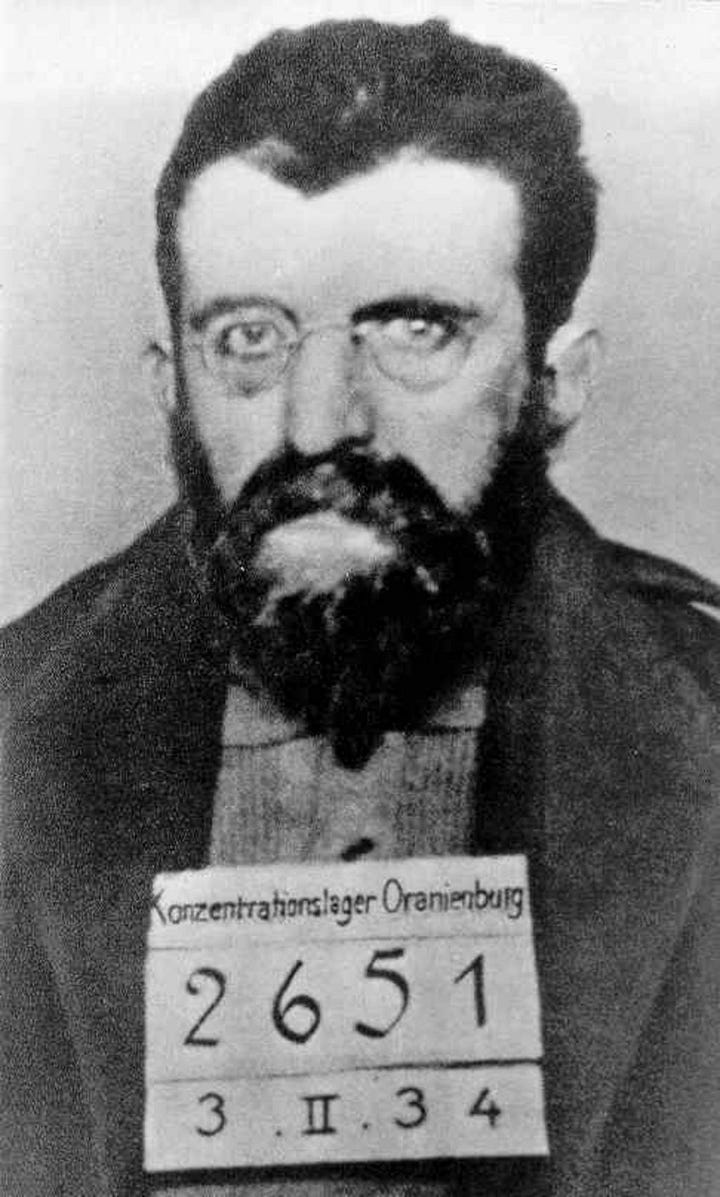

A nervous Rudolf decided to pay a visit to his friend Erich Mühsam, a Jewish anarchist poet with a knack for peppering reactionaries with scorn and biting sarcasm. For weeks Erich received threats in the mail and via telephone. Months earlier, none other than Joseph Goebbels, the Nazi Propaganda Minister, publicly (but falsely) accused Mühsam of murdering hostages back in 1919 when he had been active in the revolutionary Bavarian Council Republic. Rudolf urged his friend to leave the country right away before it was too late. Mühsam at first balked at the idea, but after Werner made a second plea, Mühsam finally prepared to leave—but not after taking care of some loose ends.

“The Reichstag Set On Fire! Mass Arrests in Berlin and Other Parts of the Country!” screamed the morning headlines on February 28, 1933. Rudolf Rocker had gone to bed early the previous day and entirely missed this bizarre event.6 A huge fire in the late evening raged through the Reichstag building. Remarkably, the arsonist was arrested while still roaming through the smoke-filled building. Marinus van der Lubbe, a Dutch émigré and Communist confessed and insisted that he had acted alone. Some people, including many anarchists, suspected that the Nazis themselves torched the building, but recent scholarship has dispelled this theory. That said, Hitler saw a political opportunity and grabbed it; privately, he called the fire a “God-given signal.”7

The next day, the government and the friendly press declared that the conflagration was the start of a vast Communist conspiracy. The ruse worked. Hitler persuaded President Hindenburg to suspend all civil liberties guaranteed by the Constitution. Mass arrests followed. “That was precisely why the situation was so dangerous,” Rocker later wrote, “for I was well aware that the Nazis could not stop halfway; they would use their undoubtedly well-prepared attack to unleash a panic in the country, which allows them to pose as the saviors of Germany and achieve the dictatorship they have wanted for so long.”8

Milly had gone out for an errand and returned home in a state of distress. Mühsam had been arrested! Why did he stay in his apartment one last night? Why did he not heed the warnings? A train ticket to Prague was in his pocket when the secret police shoved him into a car. In the following weeks, only snippets of information about Mühsam’s condition would reach the Rockers who did all they could to publicize the brutality of the regime in those early years.

There was little time to process the flow of events. Arrests were happening all over the city. It was time to go. They threw a few belongings in a bag but no suitcase, which would raise suspicion. Rudolf packed up his manuscript, Nationalism and Culture, which he completed a few days earlier, the loss of which would have been tragic. More on that later. When evening fell, they locked up their apartment and after several detours reached Werner’s house where they plotted their next move. The mood was gloomy but practical. There was no longer any hope that the labor movement could rise against the fascists. “This brown shit will poison all of Germany and half the world,” barked Werner, “the Germans will never free themselves. What is coming is a new war.”9

Rudolf and Milly realized that they did not have enough clothes for what was potentially going to be a long voyage to who knows where. Milly decided to return to their apartment one last time and come back within an hour. Rudolf endured a dreadful wait, but his fifty-five-year-old wife reappeared in time. She arranged for two friends to hand them a suitcase near the train station around nine that night. All went well. Before long, they arrived in Magdeburg, one hundred miles west, and stayed for the night. The reason for this short trip was clever; an express train to the southern border would’ve been crawling with secret agents.

Early the next morning, March 1, they were on a train to Frankfurt where they arrived in the afternoon and checked into a hotel. They found the atmosphere markedly different than in Berlin; almost normal, which was surprising given the red scare unfolding in the capital in the wake of the great fire. But was this false comfort? Was everybody asleep at the wheel? Rocker observed the following:

[in Frankfurt] you saw far fewer uniforms and people didn't look as anxious as in Berlin. Evidently, they have not fully realized the seriousness of the situation. Even in the small restaurant where we had dinner, there was a cozy atmosphere so typical of Frankfurt. The guests chatted loudly and casually, and at the table next to us, people cracked juicy Nazi jokes followed by laughter all around.10

Even the Rockers let their guard down a bit and decided to stay a few days, maybe even visit some old friends. Perhaps they could still return to their flat in Berlin when things had calmed down. But as soon as the newspapers reported the arrest of seven thousand people they decided to continue their flight and board the next train to Switzerland, a two hundred-mile journey south. And another thing: the federal elections of March 5 failed to reverse the political situation, even though the Nazis came up short of winning an absolute majority.11 After the nerve-racking customs inspection, the train pulled into Basel station.

Since the Basel train station was located in a German border enclave, Rudolf and Milly quickly traveled on to Zürich where they stayed at the Limmathaus, a sort of people’s house of the labor movement.12 Safe from arrest, the couple could now focus on improving their economic situation as well as their physical and mental well-being. Milly was not in the best of health, and they had nearly exhausted their savings. Switzerland was expensive, and soon, they made plans to venture further afield. Rudolf also remembered that anarchists and syndicalists in the United States and Canada had invited him to undertake another speaking tour in the fall.

To be continued in Part 2, coming this summer…

Rocker, Aus den Memoiren eines deutschen Anarchisten (Frankfurt: Suhrkamp Verlag, 1974), 372. All translations by the author.

David Cay Large, Berlin (Basic Books, 2000), 256.

Rocker to Nettlau, Berlin, January 20, 1933. Nettlau-Rocker-Briefwechsel, IISH.

Peter Wienand, Der “geborene” Rebell: Rudolf Rocker. Leben und Werk (Berlin: Kramer Verlag, 1981), 364.

Rocker to Nettlau, Zürich, March 11, 1933. Nettlau-Rocker-Briefwechsel, IISH.

Rocker, Aus den Memoiren, 364.

Large, Berlin, 261.

Rocker, Aus den Memoiren, 365.

Rocker, Aus den Memoiren, 368.

Rocker, Aus den Memoiren, 372.

Rocker, Aus den Memoiren, 369-372.

Rocker to Nettlau, Zürich, March 11, 1933. Nettlau-Rocker-Briefwechsel, IISH.