Milly and Rudolf Rocker stayed in Zürich for at least ten days, offering time for reflection. Rudolf had been writing for years about the existential dangers of nationalism and the nation-state, and now his theories were being put into practice with terrifying accuracy. His premise is simple. States concentrate power and monopolize violence, whether they are democratic or autocratic. States are machines that can be automated and leveraged. Big states are infinitely more dangerous because one party can use democratic means to amass the means of power and become nearly omnipotent. Within a state, in other words, the transition from democracy to autocracy is much more fluid than people like to admit, especially people who don’t question the presence of the state apparatus.

Rudolf tried to remain optimistic despite believing Germany was descending into madness. “It’s getting darker and darker in the world,” he once wrote, “but one mustn’t lose courage, and especially today it’s important to uphold the idea of freedom so that everything doesn’t perish in this time of severe hardship.”1 There were no silver linings for Milly; she saw disaster around every corner.

One day, an invitation arrived from Emma Goldman. Would Milly and Rudolf like to spend time at Bon Esprit, Goldman’s cottage near St. Tropez on the French Côte d’Azur? It would be a quiet retreat with a view of the small harbor and the Mediterranean. The Rockers arrived in southern France sometime in mid-March when Hitler officially proclaimed the Third Reich. They enjoyed about six weeks of rest with good friends. On March 25, Rudolf Rocker celebrated his sixtieth birthday. Two days earlier, the German parliament passed a “Law to Remedy the Distress of the People and the Reich,” better known as the Enabling Act, which allowed Hitler to enact laws without anyone else’s approval.

But the real distress was the rapid erosion of freedom and the normalization of violence and brutality. How did we get here? Did it come as a surprise? Or had the pump been primed a long time ago?

Under the Mediterranean sun, Rudolf recounted his recent experiences, which grew into an essay called The Road to the Third Reich (Der Weg ins Dritte Reich). Let’s do a brief reading because, in this essay, Rocker repeats some of the most compelling arguments of twentieth-century anarchism that anyone interested in politics ought to know. He denounced the socialists and communists for their failure to resist fascism. He argued that any striving for political power—usually embodied in a state—from the left or the right would invariably open the door to despotism. It is all good and well that socialism fights against economic exploitation and the monopoly of property, but if it refrains from attacking domination itself, it will simply become the next authoritarian wasteland. Russia was a case in point.

Not the conquest of the principle of power, but eliminating it from society must remain the great goal of [socialism]. Anyone who believes that personal freedom can be replaced by equality of interests has never grasped the true essence of socialism. There is no substitute for freedom; there never can be [...] Socialism means working together in solidarity for a common goal and the same rights for everyone. Solidarity, however, is based on free decision and cannot be enforced unless it wants to be tyranny and thus abolish itself. —Rudolf Rocker2

Rocker made an explicit connection between fascism and Stalinism, between the rise of despotism under Lenin and fascism under Hitler and Mussolini. The will to state power, which often begins with the language of nationalism and patriotism, is palpable within both the extreme Right and Left. It was not surprising to Rocker that several local branches of the Communist Party had joined Hitler’s stormtroopers. This viewpoint about the political Left and Right was rather unorthodox during the 1930s when most of the Left—except for the anarchists—combined (with a straight face) virulent antifascism with a wholly uncritical reverence for Stalin’s Russia.

The terrible events in Germany have only allowed these brave Soviet followers to stress the need for a counter-dictatorship as the only remedy that can supposedly liberate the world. —Rudolf Rocker3

As storm clouds gathered over Europe, Milly and Rudolf accepted the invitation for a lecture tour during the upcoming fall in Canada and possibly the United States. This move could bring in some cash and, more importantly, reunite them with their younger son Fermin, who was a graphic designer in the United States. Immigrating to America was out of the question, so securing a permanent residency permit in a European state was the pressing issue.

A political reversal or stabilization in Germany seemed unthinkable. Rocker predicted with eery foresight that Hitler would rekindle German industries to tackle unemployment and re-arm and prepare for war. What about France? The Rockers traveled to Paris for answers but were told that legal residency was unlikely, let alone a work permit (he had been expelled in 1894). Smaller democracies like Switzerland and Belgium kept their doors closed out of fear of German intimidation, and Holland may offer residency but no work permit.

Britain and Spain beckoned as the most reasonable destinations. The Rockers had many friends in Spain, most connected with the anarcho-syndicalist movement, which was then the largest and most active in the world. But revolutionary foreigners were not always welcome even there, according to their friend Helmut Rüdiger. Eventually, Britain’s Labour government granted them a two-month stay, which they were able to extend by a month.

Terrible news greeted Milly and Rudolf shortly after arriving in London in May 1933. The police had broken into their Berlin apartment and confiscated their entire library—some five thousand volumes. Worse was that Ernst Simmerling, a friend and relative, had been in the apartment and was never heard from again. For a scholar like Rocker, losing all those resources was devastating. “I am in a state of mental depression like never before,” he wrote to Goldman. “I don’t need to tell you what losing my library means. Many future literary plans will have to be abandoned forever […] I feel like someone without air to breathe.”4 The Nazis also sealed the room so that nothing could ever be retrieved.

Rudolf only learned later that not all was lost. In one of those unsung, heroic actions, Simmerling, Fritz Kater, Arthur Lehning, and Anton Bakels managed to haul away a large portion of Rocker’s library in the weeks before the Nazi raid. They then sent the boxes to Amsterdam, where they became part of the now-famous International Institute of Social History.

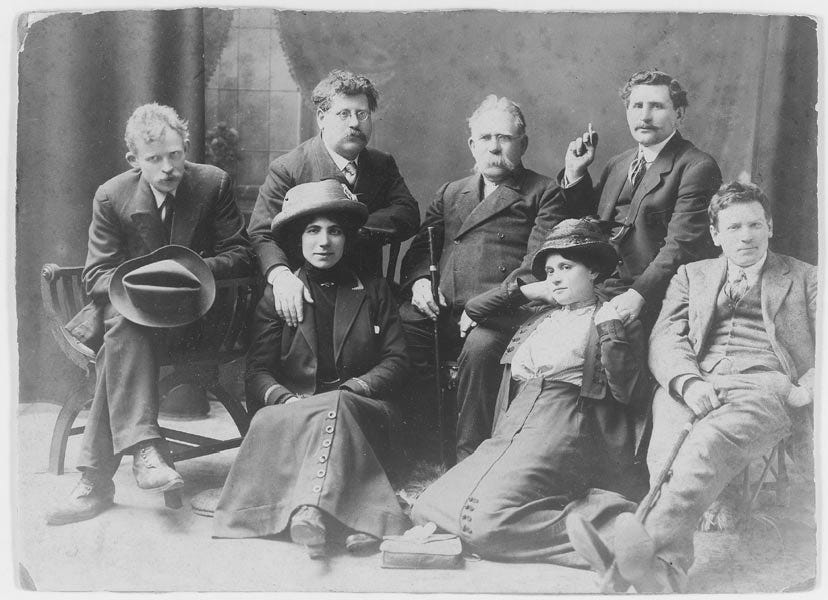

London was emotional for other reasons. It was the city where Milly and Rudolf met some thirty-six years ago and where both had worked tirelessly among the Jewish workers for over twenty years. Upon arrival, they received a welcome party where ₤30 was collected for Erich Mühsam and other comrades in Nazi jails.5 Also, Milly’s sister and parents still lived in the same East End neighborhood. “A strange feeling crept over us as we saw the old places where we had lived and worked for so many years,” remembered Rudolf.6

But those old places were just that; hardly any anarchist movement was left. Milly and Rudolf shared their disappointment with Emma Goldman, who believed they would be more useful in the United States rather than settle in London and rebuild the movement. But the insecurities of their nomadic life for the past six months were taking a toll. “If I’m honest,” he said to Goldman, “I urgently need to find solid ground under my feet again.”7

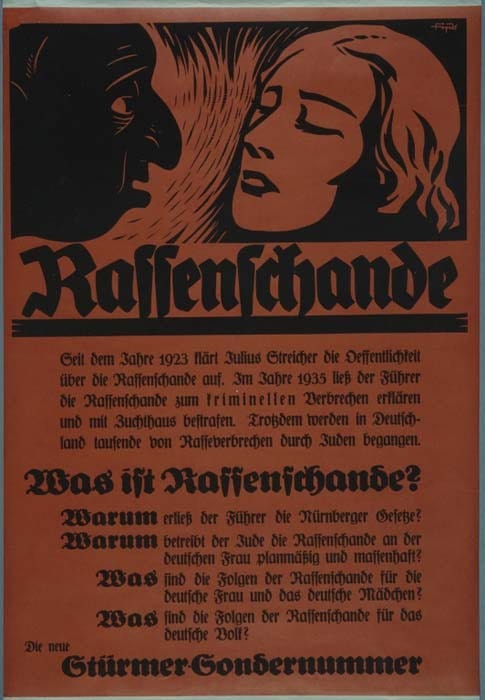

The rise of antisemitism was of particular concern to the Rockers. As they pitched their tent in London, the Nazis criminalized any marriage between a German and a Jewish or non-white person. Antisemitism and racism are not simply caused by economic inequalities or anxieties, and that, according to Milly and Rudolf, made them so dangerous. There is a psychology that shows that we are not born with this kind of hatred; we are taught it. This insight led Rocker to conclude that “the attitude of a people towards the Jews is [...] a measure of its democratic and liberal spirit and its capacity for further progress.”8

Despite Goldman’s advice, Rudolf Rocker, still upset about losing his books, lost all appetite for a lecture tour in America. Letters from comrades painted a pessimistic picture: massive unemployment, the dollar in free fall, and no one having any money to contribute to the movement. A sense of hope hanging by a thread and powerlessness emanates from Milly and Rudolf’s letters to friends. “It’s a wicked world we’ve fallen into,” he wrote to Goldman, “and who knows what the future may hold in store.”9 Milly was also in a bad place, and they decided to travel briefly to France and Spain for a change of scenery. What added to their anguish was that no one in the rest of the world seemed to realize how dangerous things had gotten in Hitler’s Germany.

By June 1933, Milly and Rudolf prepared to depart for North America in September. There had been some job offerings, either at a syndicalist union or as editor, but Rudolf preferred to remain independent. He was offered the editorship of Fraye Arbeter Shtime (Free Voice of Labor) in New York, the foremost Yiddish anarchist paper in the world, but he declined. At one point, Nettlau suggested Rocker revive John Most’s classic paper Freiheit, which ran from 1879 to 1910 in London and then in New York. But Rocker could not envision settling in depression-era America. “I’m too European to settle permanently in America,” he wrote Nettlau, “even if immigration laws would allow it. No, that is really out of the question.”10 An extended visit was all he could bear.

Gaining entry into the United States was surprisingly painless; at the end of July, they were granted a visitor visa valid for six months. On August 26, Milly and Rudolf boarded the steamship Statendam in Southampton, bound for New York.

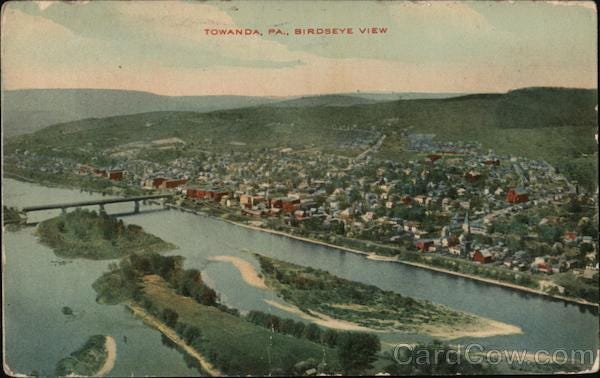

Eight days later, they were greeted by their son Fermin, Milly’s sister Fanny and her husband, Morris Pokrass. They spent ten days in a housing complex on Grand Street on the Lower East Side, a deary, characterless place, after which they traveled to Fanny and Morris’s home in Towanda, a small town on the Susquehanna River in northern Pennsylvania.11 The remote rural setting was most welcome, but as soon as they settled, Rudolf had to undergo eye surgery resulting from an untreated infection he contracted in London. After a quick recovery, the Rockers could enjoy some happiness in an otherwise gloomy world.12

My wife and I go for walks in the mountains daily; there is also a wonderfully situated mountain lake, which I have already swum lengthwise and widthwise. But don’t worry; I’m always accompanied by a boat, so nothing can happen. The weather and the water are still warm, making it a pleasure to splash around. —Rudolf Rocker13

Rudolf Rocker’s lecture tour began on October 6, 1933, in New York and would take him to the West Coast and the principal cities in Canada. The Rockers soon found themselves in a distressing position again. As the situation in Germany and the rest of Europe grew grimmer by the day, any prospect of returning to a safe place in Europe faded. At the same time, maintaining legal status in the United States became a nerve-racking, nail-biting slog of requesting and waiting for visa extensions—a story for another time.

After all these peregrinations, the most priceless item the Rockers denied the Nazis was the manuscript of Nationalism and Culture, published in Los Angeles in 1937, which became a classic praised by Bertrand Russell, Albert Einstein, and Thomas Mann.

The manuscript and its bearer outwitted and survived the book burners, and if for no other reason, you should read it or listen to it.

Rocker to Nettlau, Zürich, March 11, 1933.

Rocker, “Der Weg ins Dritte Reich: Die kommunistische Partei und die Idee der Diktatur,” Die Internationale ,Neue Folge, Vol. 1, Nr. 2 (Oct-Nov, 1934), pp.33–37.

Rocker to Goldman, Towanda, September 23, 1933, Emma Goldman Papers, IISH.

Rocker to Goldman, London, May 5, 1933, Emma Goldman Papers, IISH.

Rocker to Nettlau, London, May 10, 1933.

Quoted in Werner Portmann and Siegbert Wolf, “’Die Tore der Freiheit öffnen’: Milly Witkop-Rocker (1877-1955), Anarchistin und Feministin,” In: “Ja, ich kämpte” Von Revolutionsträumen, ‘Luftmenschen’ und Kindern des Schtetls. Biographien radikaler Jüdinnen und Juden (Münster: Unrast, 2006), 286.

Rocker to Goldman, London, August 23, 1933, Emma Goldman Papers, IISH; Peter Wienand, Der “geborene” Rebell: Rudolf Rocker. Leben und Werk (Berlin: Karin Kramer Verlag, 1981), 385.

Rocker, Kritische Betrachtungen über die Judenfrage, quoted in Portmann & Wolf, 287.

Rocker to Goldman, London, May 5, 1933, Emma Goldman Papers, IISH.

Rocker to Nettlau, Paris, June 12, 1933.

Interview with Fermin Rocker, in Paul Avrich, ed., Anarchist Voices: An Oral History of Anarchism in America (1995; AK Press, 2005), 37.

Rocker to Nettlau, Towanda, September 27, 1933.

Rocker to Nettlau, Towanda, September 27, 1933.