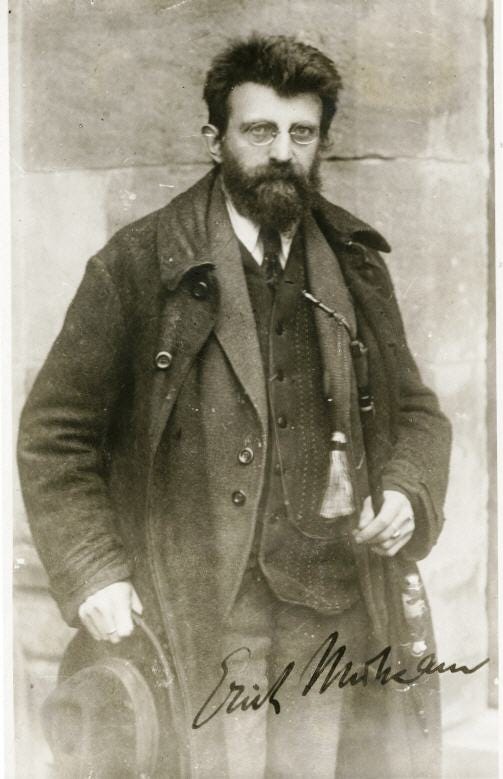

Erich Mühsam, the German anarchist poet and playwright, put down his diary in November 1912, only to pick it up again on August 3, 1914, the day Germany declared war on France and invaded neutral Belgium. Trained as a pharmacist, Mühsam soon found himself drawn to radical politics and the bohemian circles of Berlin and Munich, where he settled in 1906. He founded the anarchist group Tat (“Deed”) during the unemployment crisis of 1909 and, in 1911, launched Kain, a monthly anarchist literary magazine known for its biting sarcasm. For Mühsam, poets and artists of all kinds were meant to be activists in the fight against oppression and injustice.

Mühsam’s compelling diaries, now transcribed and searchable in German, offer a unique glimpse into his revolutionary mind. Below is one translated entry, with footnotes sourced from the Erich Mühsam Tagebücher website unless otherwise noted.

And now, I give you Erich Mühsam:

Munich, Monday/Tuesday, August 3/4, 1914.

It is 1 o'clock at night. The sky is clear and full of stars, but above the Academy1 looms the edge of a white cloud piled in thick layers, incessantly flashing with lightning. The lightning is uncanny, glaring, lingering, running horizontally.

And there is war. All that is terrible is unleashed. For a week, the world has been transformed. For three days, the gods have raged. How dreadful these times are! How terrifyingly close death is to all of us!

The thought of war has always occupied my mind. I tried to picture it with all its horrors; I wrote against it, believing I understood its frightfulness.

Now it is here. I see strong, beautiful people, individually and in groups, passing through the streets, ready for war. I shake hands with dozens daily to say goodbye; I know close friends and acquaintances are on their way to the front or preparing to go — Körting, Kutscher, Bötticher, von Jacobi, both sons of Max Halbe, and many more.2 I know that many will not return. I read dispatches and news that — even now, before the catastrophe has begun — make one’s heart cry out. I see everything horribly close, and it is much worse in reality than my theorizing imagination had conceived. And I, the anarchist, the anti-militarist, the enemy of national phrases, the anti-patriot, and the hateful critic of the arms frenzy — I catch myself somehow gripped by the general frenzy, ignited by angry passion, even if not against any “enemies,” but filled with the burning desire that “we” save ourselves from them! Only: who are they — who is “we”?

But isn’t it a ghastly thought that the Russians could come into the country? Barbarians? Nevertheless, people of a different kind, without respect for our world, killing and burning without consideration for our feelings, mistreating women and children, and making Cossack jokes with our cultural treasures. And how terrible it is to read that today a French doctor with two officers in Metz tried to poison a well with cholera bacilli!* The day before yesterday, the hands of a chauvinist murdered Jaurès, the man who wanted peace, who essentially embodied what we revere as superior French culture.3 And now French planes are crossing the country and dropping bombs. Theories abandon you; you become one of everyone, with everyone’s instincts, but with increased suffering because the critique remains effective alongside the feeling, and because all partisanship belongs to the victims, not the perpetrators.

The masses have gone into a true hysteria due to the excitement of these days. Spies are suspected everywhere. Then people rush together in crowds, mistreat the unfortunate, and hand them over to the police. Sometimes, it is said that real Russian bomb-throwers have already been caught — Rosenthal4 just told at the Torggelhaus5 that 28 Russians, disguised as women or priests, were arrested at the station today — but most of the time, innocents suffer. Yesterday, I rescued the excessively made-up Frau Dr. Douglas-Andree from such a situation.6 She was mistaken for a disguised man. I intervened, identified her, and walked with her and poor Addi, her 15-year-old son, to the nearest car, followed by yelling, cursing, and excessively excited crowds.7 As soon as she sat in the car and wanted to leave, people blocked the way, and although I and the waiters at Stefanie8 declared that we knew the woman, two soldiers were requisitioned to accompany her in the car to the barracks. This morning, I saw a somewhat foreign-looking couple hastily fleeing through the streets, chased by an excited crowd. I do not know what became of them. And in the afternoon, in Sendlingerstrasse, hundreds once again brought a girl to a policeman, claiming it was a disguised man.

Wild rumors are circulating uncontrollably because the authorities remain silent about almost everything. According to these rumors, yesterday and today a whole bunch of Serbs and Russians were summarily executed here. They are said to have attempted to blow up the main post office, the train station, and the powder tower near Freymann. This morning, it was spread that the tap water was poisoned. Officers shouted warnings — I witnessed it myself — and houses were individually notified. It turned out to be idle talk. One hears — very secretly — about mass soldier suicides, etc.

And yet, despite all delusion, the unanimity of feeling that a just cause is being fought is moving. People are very serious, but visibly elevated. If only there hadn’t already been a noticeable bad atmosphere everywhere of sniffing out everyone’s convictions! The night before last, I met Köhler, von Maaßen, and Bötticher in the large room of the Torggelstube.9 My appearance caused suspicion among the surrounding national students, who eavesdropped on us and, although not a word was spoken that could have hurt feelings, denounced us. There were heated disputes. Maaßen handed out slaps. Eventually, Bötticher — on the day before his departure to the Navy! — was taken away (though released again on the street), and I was insulted and threatened. Without having spoken a single political word!

Today, I issued a statement10 to the readers of Kain11 explaining that I am suspending the paper for the duration of the war. Furthermore, I have registered as an auxiliary worker in the registry at the Schwabinger Hospital. Where everything is in flux, and I might not know how to make a living tomorrow, I do not want to be idle. If I receive no or a negative answer, I will go to the magistrate tomorrow and inquire about employment in humanitarian civilian service: with the sick, the insane, or the fire brigade. Perhaps my old experience as a pharmacist can also be of use there.

I am very worried about Jenny12 The last news I received was on July 29th, still from Eydtkuhnen, which is now occupied by the Russians.13 A telegram in which she asked me to write to her by general delivery in Königsberg.14 I did so immediately, but in the meantime, I have read that the general delivery of letters is now either suspended or severely restricted. Now I do not even know where my beloved is, and I am very anxious. If the general tension allowed me to reflect on personal matters, I think I would die of restlessness.

I hear nothing from Lübeck either. The Landsturm15 has been called up, and I fear that my two brothers-in-law and perhaps even my brother16 will have to go to the front. That would be very hard for our old father17 — and Charlotte18 has just given birth to her third child. But what does that say compared to the fate of poor Lucie von Jacobi19 who lost her only child half a year ago and now sees her husband going off to war!

Tomorrow, the war with France is expected to officially begin. Telegrams have been posted stating that the ambassador in Paris has been asked to request his passports because the French have violated international law by crossing the borders. Libau20 is said to have been shelled by a small cruiser, and the naval base is said to be burning. That would be a success for the Germans. How to evaluate the Russians' march into Eydtkuhnen and the Germans' into Czenstochau is not yet clear at all. For now, everything is greeted with cheers.

Rosenthal claimed to know that the Louvre in Paris is burning. I don’t believe it. But how hideous already that it could even become possible!

* False report. Denied

Academy of Fine Arts building in the Maxvorstadt district in Munich. Mühsam lived across the street on Akademiestrasse. [my note]

Berthold Körting (1883-1930), painter and architect; member of the “Hermetischen Gesellschaft;” married to Helene Körting. Artur Kutscher (1878-1960), literary and theater scholar at the University of Munich; led the so-called "Kutscher Seminar," which focused on contemporary literature and also invited Erich Mühsam for readings. Hans Gustav Bötticher (1883-1934) went by Joachim Ringelnatz. Bernhard von Jacobi (1880-1914), stage actor at the Munich Hoftheater. Max Halbe (1865-1944), German writer and bohemian; became known as a dramatist for naturalism (Jugend, 1893).

Jean Jaurès (1859-1914), French socialist and pacifist politician, he fell victim to a nationalist assassination shortly before the outbreak of the First World War.

Dr. Wilhelm Rosenthal (1870-1933), since 1896, he was a lawyer in Munich, legal advisor for the Neuen Vereins (New Association), and co-founder of the Drei Masken Verlag (Three Masks Publishing), the Künstler-Theater in Munich, and other cultural enterprises.

Torggelstube, a wine bar located next to the Hofbräuhaus in Munich. [my note]

Martha Douglas-André (1867-?), a writer who published several books under the name M. C. André with Douglas Verlag in Munich. She was the wife (and from 1911, the widow) of the publisher Dr. Robert Douglas and the mother of Adi. Also known as André-Douglas.

Adalbert Douglas-André (1897-1924), also called Adi or Addi, son of Martha Douglas-André from a first marriage. Else Lasker-Schüler dedicated a poem to him.

Café Stefanie in Munich was a coffeehouse frequented by artists and bohemians on the corner of Amalienstrasse and Theresienstrasse.

Bernhard Köhler (1882-1939), reviewer for the Berner Zeitung, volunteer soldier in World War I, and co-founder of the Nazi Party after the war. Carl Georg von Maassen (1880-1940), Literary historian, book collector, and long-time friend of Mühsam. For Mühsam's letters to Maassen, see Erich Mühsam, Briefe 1900–1934, edited by Gerd W. Jungblut, Vaduz, 1984.

At the outbreak of the First World War, Mühsam announced in a public statement that the magazine would suspend publication for the duration of the war. The original version of this statement (shortened in the München-Augsburger Abendzeitung on August 24, 1914) contained the following sentences, which Mühsam removed from a revised edition later in August: “For now, let all discord rest in the land. The principles of my convictions are not affected by the current events. But I find myself united with all Germans in the hope that we will succeed in keeping the foreign hordes away from our children and women, our cities and fields.”

Kain. Zeitschrift für Menschlichkeit [Kain: Journal for Humanity] was a magazine edited and largely managed by Mühsam. It was published monthly from April 1911 to July 1914 and irregularly from December 1918 to April 1919, under the title Revolutionskain. The magazine served as a platform for Mühsam’s anarchist ideas, advocating for humanity, social justice, and anti-authoritarianism.

Jenny Brünn (1892–1928) studied economics in Munich, Königsberg, and Berlin, and completed her doctorate in Würzburg in 1918 with a dissertation titled “Das Problem der komparativen Statik, erläutert an Ricardos Verteilungstheorie, insbesondere an seiner Lohnlehre” (The Problem of Comparative Statics, Explained Using Ricardo's Theory of Distribution, Particularly His Wage Theory). She was actively involved with the "Gruppe Tat" and became Erich Mühsam's fiancée. In 1918/19, she published in Kain, and continued her work as a leftist publicist throughout the 1920s.

Eydtkuhnen (now Chernyshevskoye) was an important border crossing in East Prussia between Russia and Germany. [my note]

Now Kaliningrad in Russia. [my note]

the militia [my note]

Hans Mühsam (1876–1957), brother of Erich Mühsam, was a physician who practiced in Charlottenburg, Berlin. He served as the head of the Berlin "Jüdischer Volksverein" (Jewish People's Association) and was an active Zionist. He was also a close friend of Albert Einstein.

Siegfried Seligmann Mühsam (born September 2, 1838, in Berlin – died July 20, 1915, in Lübeck) was the father of Erich Mühsam. He was a pharmacist who settled in Lübeck in 1878. Siegfried was an active member of the Lübeck Bürgerschaft (City Council), the Gemeinnützige Gesellschaft (Society for the Common Good), and the Freemason Lodge "Zur Weltkugel" (To the Globe).

Charlotte Landau (née Mühsam, 1881–1972) was the younger sister of Erich Mühsam. She was married to Leo Landau, a lawyer in Lübeck. Charlotte authored "Meine Erinnerungen" (My Memories), which was edited by Peter Guttkuhn and published as part of the writings of the Erich-Mühsam-Gesellschaft, Heft 34, in Lübeck in 2010.

Lucy von Jacobi (née Geldern, 1887–1956) was an actress who later became a journalist. She was married to Bernhard von Jacobi.

Libau (now Liepāja in Latvia) served as a Russian naval base during World War I. On August 2, 1914, it was shelled by the German cruisers Augsburg and Magdeburg.